Problem #DES-PigeonholeNT

Problem

One of the most important tools in maths is the Pigeonhole Principle.

You may have already met it before, but if not, let’s recap it quickly.

Simply put: the Pigeonhole Principle states that if you have \(n\) pigeons (or objects) that you want to

place into a number of pigeonholes (or containers) that is strictly

smaller than \(n\), e.g: \(10\) pigeons but only \(9\) pigeonholes, then there will be a

pigeonhole with at least two pigeons. Why is this true? Imagine that

every pigeonhole had at most one pigeon. Since we have \(9\) pigenholes in total, there would be at

most \(9\) pigeons, not \(10\), as we are told. Today we will see how

this principle can be used to solve problems about numbers and their

divisibility properties.

Before we get started, we need to recap a very important concept: if we

have two numbers, say \(a\) and \(b\), we can divide \(a\) by \(b\), and we will obtain a quotient

\(q\) and a remainder \(r\), and write \[a=q\times b + r\] for example: if we

divide \(9\) by \(4\), we can write \(9=2\times 4 + 1\), i.e: the quotient will

be \(2\) and the remainder will be

\(1\). A final key fact that we need to

recap is the following: imagine we want to divide two numbers, for

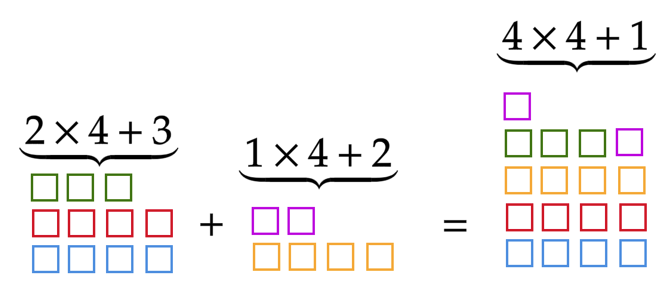

example \(11\) and \(6\) by the same number, say \(4\). We can write \[11=2\times 4 + 3\qquad \text{and}\qquad 6=1\times

4 + 2\] So we can imagine \(11\)

as two packs of \(4\) little squares

and \(3\) “left over" squares, and

\(6\) as one pack of four little

squares with \(2\) left over squares.

We can combine these \(5\) “left over"

squares into one new pack of four, with now one “left" over square. With

this way of thinking, we see that the remainder of a sum of two

numbers \(a\) and \(b\) is precisely the remainder of the

sum of the remainder of \(a\) plus

the remainder of \(b\).

A final remark: in today’s sheet, when we say positive whole numbers, or natural numbers, we will mean the numbers \(1,2,\cdots\)