Problems

Show that there are infinitely many composite numbers \(n\) such that \(3^{n-1}-2^{n-1}\) is divisible by \(n\).

Show that there are infinitely many integers \(n\) such that \(2^n+1\) is divisible by \(n\). Find all prime numbers that satisfy this property.

If \(k>1\), show that \(k\) does not divide \(2^{k-1}+1\). Find all prime numbers \(p,q\) such that \(2^p+2^q\) is divisible by \(pq\).

Find all pairs \((x,n)\) of positive integers such that \(x^n + 2^n + 1\) is a divisor of \(x^{n+1} + 2^{n+1} + 1\).

Let \(n>1\) be an integer. Show that \(n\) does not divide \(2^n-1\).

Find all integers \(n\) such that \(1^n + 2^n + ... + (n-1)^n\) is divisible by \(n\).

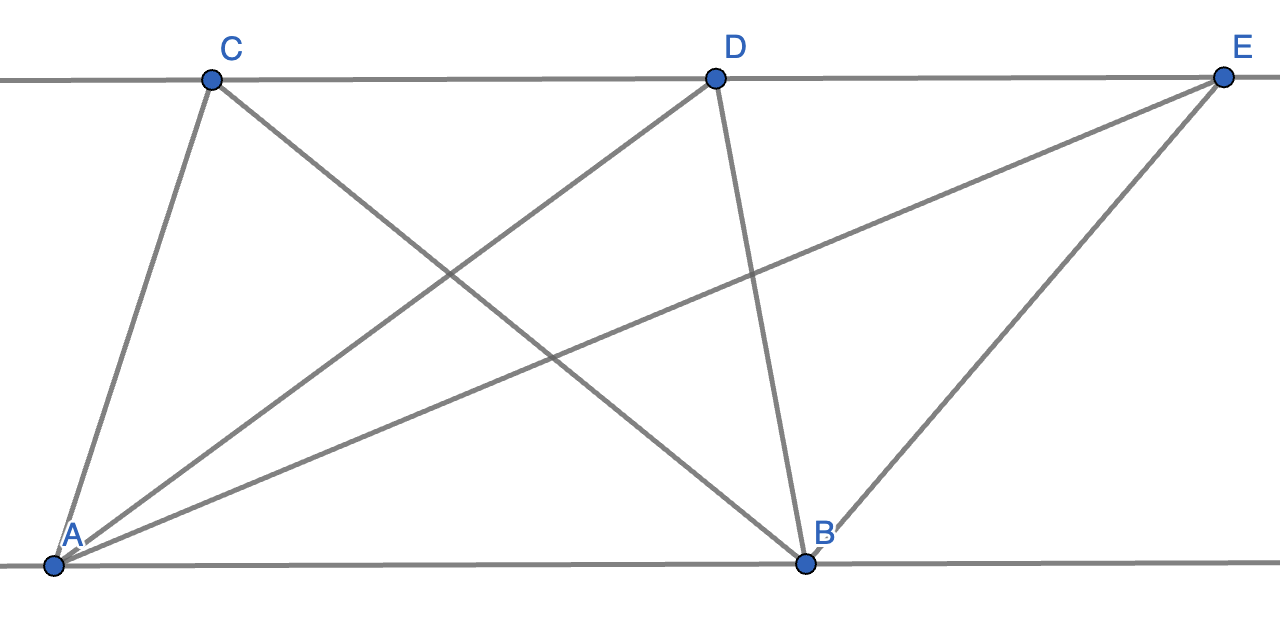

Lines \(AB\) and \(CDE\) are parallel. Which triangle out of \(\triangle ABC\), \(\triangle ABD\) and \(\triangle ABE\) has the greatest area?

Let \(u\) and \(v\) be two positive integers, with \(u>v\). Prove that a triangle with side lengths \(u^2-v^2\), \(2uv\) and \(u^2+v^2\) is right-angled.

We call a triple of natural numbers (also known as positive integers) \((a,b,c)\) satisfying \(a^2+b^2=c^2\) a Pythagorean triple. If, further, \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\) are relatively prime, then we say that \((a,b,c)\) is a primitive Pythagorean triple.

Show that every primitive Pythagorean triple can be written in the form \((u^2-v^2,2uv,u^2+v^2)\) for some coprime positive integers \(u>v\).