Problems

A rook in chess can move any number of squares in the same row or column. Let’s invent a new figure, a “little rook" that can only move one square in each of these directions. If we start with the "little rook" in the bottom right corner of an \(8 \times 8\) chessboard, can we make it to the top left corner while visiting each square exactly once?

There are \(15\) lightbulbs in a row, all switched off. In one move, we may choose any three bulbs and change their state (on becomes off, and off becomes on).

Is it possible to repeat this move an even number of times and end up with all \(15\) lightbulbs switched on?

The numbers \(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\) and \(10\) are written on a board.

In one move, you may erase any three of the remaining numbers, call them \(a,b\) and \(c\), and replace them with the three numbers \(2a+b,\; 2b+c\) and \(2c+a\).

Is it possible, after a sequence of such moves, for all \(10\) numbers on the board to be equal?

On a certain island there are \(17\) grey, \(15\) brown and \(13\) crimson chameleons. If two chameleons of different colours meet, then both of them change into the third colour. No other colour changes are allowed. Is it possible that, after a number of such colour changes, all the chameleons have the same colour?

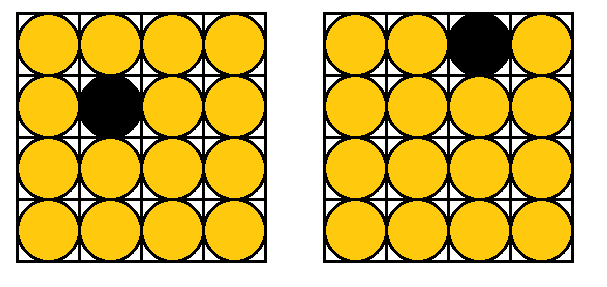

Sixteen lightbulbs are arranged in a \(4 \times 4\) grid. Some of them are on, the other ones are off. You are allowed to change the state of all the bulbs in a column, in a row, or along any diagonal (note: there are \(14\) diagonals in total!). Is it possible to go from the arrangement on the left to the one on the right by repeating this operation?

The numbers \(1\) to \(2025\) are written on a board. In one move, we may erase any two numbers and replace them with the absolute value of their difference. Can we, after some number of moves, end up with a sequence consisting only of \(0\)?

Hard. Let \(\mathcal{S}\) be a finite set of at least two points in the plane. Assume that no three points of \(\mathcal S\) are collinear. A windmill is a process that starts with a line \(\ell\) going through a single point \(P \in \mathcal S\). The line rotates clockwise about the pivot \(P\) until the first time that the line meets some other point belonging to \(\mathcal S\). This point, \(Q\), takes over as the new pivot, and the line now rotates clockwise about \(Q\), until it next meets a point of \(\mathcal S\). This process continues indefinitely. Show that we can choose a point \(P\) in \(\mathcal S\) and a line \(\ell\) going through \(P\) such that the resulting windmill uses each point of \(\mathcal S\) as a pivot infinitely many times.

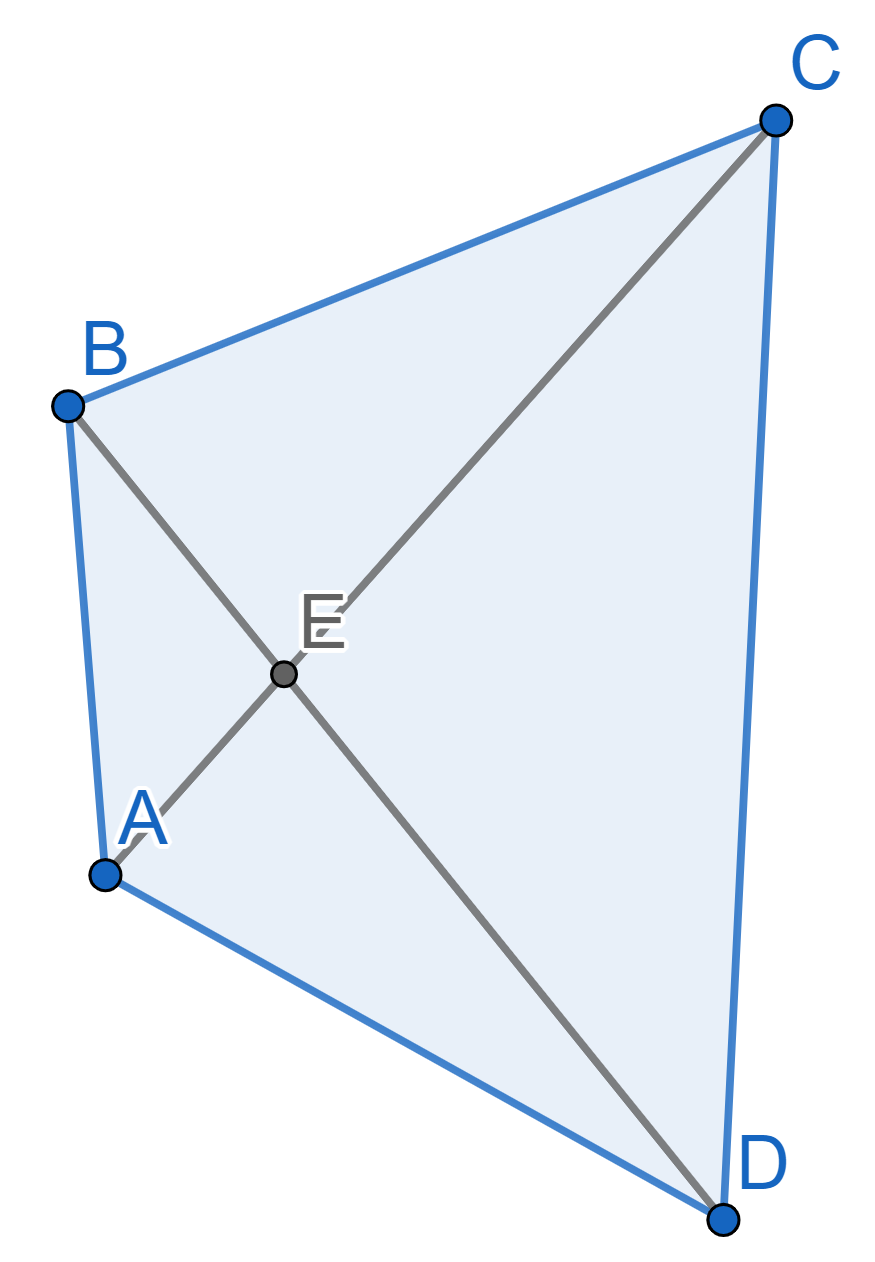

In the quadrilateral \(ABCD\) the

diagonals \(AC\) and \(BD\) intersect at the point \(E\). It is known that the perimeter of the

triangle \(ABC\) is equal to the

perimeter of the triangle \(ABD\), and

the perimeter of the triangle \(ACD\)

equals the perimeter of the triangle \(BCD\).

Prove that \(AE=BE\).

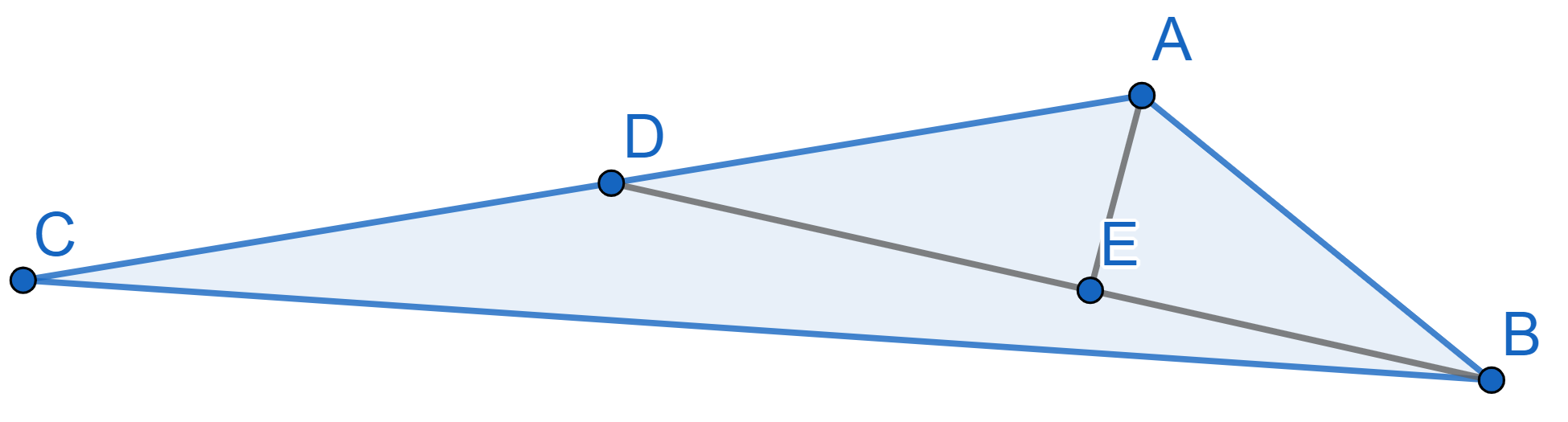

In the triangle \(ABC\) the segment

\(AB=5\) and the segment \(BD\) is the median. The segment \(AE\) is perpendicular to \(BD\) and divides \(BD\) in half. Find the length of \(AC\).

A magic square is a square filled with numbers, one in each cell, in such a way that the sums of the numbers in each row, each column and along each of the two main diagonals are the same. The value of this sum is known as the magic constant of the square. Show that in any \(4 \times 4\) magic square (which contains \(16\) numbers) the sum of all the numbers in the \(4\) central squares is also equal to the magic constant of the square.