Problems

A sequence of natural numbers \(a_1 < a_2 < a_3 < \dots < a_n < \dots\) is such that each natural number is either a term in the sequence, can be expressed as the sum of two terms in the sequence, or perhaps the same term twice. Prove that \(a_n \leq n^2\) for any \(n=1, 2, 3,\dots\)

Out of the given numbers 1, 2, 3, ..., 1000, find the largest number \(m\) that has this property: no matter which \(m\) of these numbers you delete, among the remaining \(1000 - m\) numbers there are two, of which one is divisible by the other.

Let’s call a natural number good if in its decimal record we have the numbers 1, 9, 7, 3 in succession, and bad if otherwise. (For example, the number 197,639,917 is bad and the number 116,519,732 is good.) Prove that there exists a positive integer \(n\) such that among all \(n\)-digit numbers (from \(10^{n-1}\) to \(10^{n-1}\)) there are more good than bad numbers.

Try to find the smallest possible \(n\).

An infinite sequence of digits is given. One may consider a finite set of consecutive digits and view it as a number in decimal expression, whose digits shall be read from left to right, as usual. Prove that, for any natural number \(n\) which is relatively prime with 10, you can choose a finite set of consecutive digits which gives you a multiple of \(n\).

Author: A.A. Egorov

Calculate the square root of the number \(0.111 \dots 111\) (100 ones) to within a) 100; b) 101; c)* 200 decimal places.

Author: V.A. Popov

On the interval \([0; 1]\) a function \(f\) is given. This function is non-negative at all points, \(f (1) = 1\) and, finally, for any two non-negative numbers \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) whose sum does not exceed 1, the quantity \(f (x_1 + x_2)\) does not exceed the sum of \(f (x_1)\) and \(f (x_2)\).

a) Prove that for any number \(x\) on the interval \([0; 1]\), the inequality \(f (x_2) \leq 2x\) holds.

b) Prove that for any number \(x\) on the interval \([0; 1]\), the \(f (x_2) \leq 1.9x\) must be true?

The triangle \(C_1C_2O\) is given. Within it the bisector \(C_2C_3\) is drawn, then in the triangle \(C_2C_3O\) – bisector \(C_3C_4\) and so on. Prove that the sequence of angles \(\gamma_n = C_{n + 1}C_nO\) tends to a limit, and find this limit if \(C_1OC_2 = \alpha\).

A rectangular chocolate bar size \(5 \times 10\) is divided by vertical and horizontal division lines into 50 square pieces. Two players are playing the following game. The one who starts breaks the chocolate bar along some division line into two rectangular pieces and puts the resulting pieces on the table. Then players take turns doing the same operation: each time the player whose turn it is at the moment breaks one of the parts into two parts. The one who is the first to break off a square slice \(1\times 1\) (without division lines) a) loses; b) wins. Which of the players can secure a win: the one who starts or the other one?

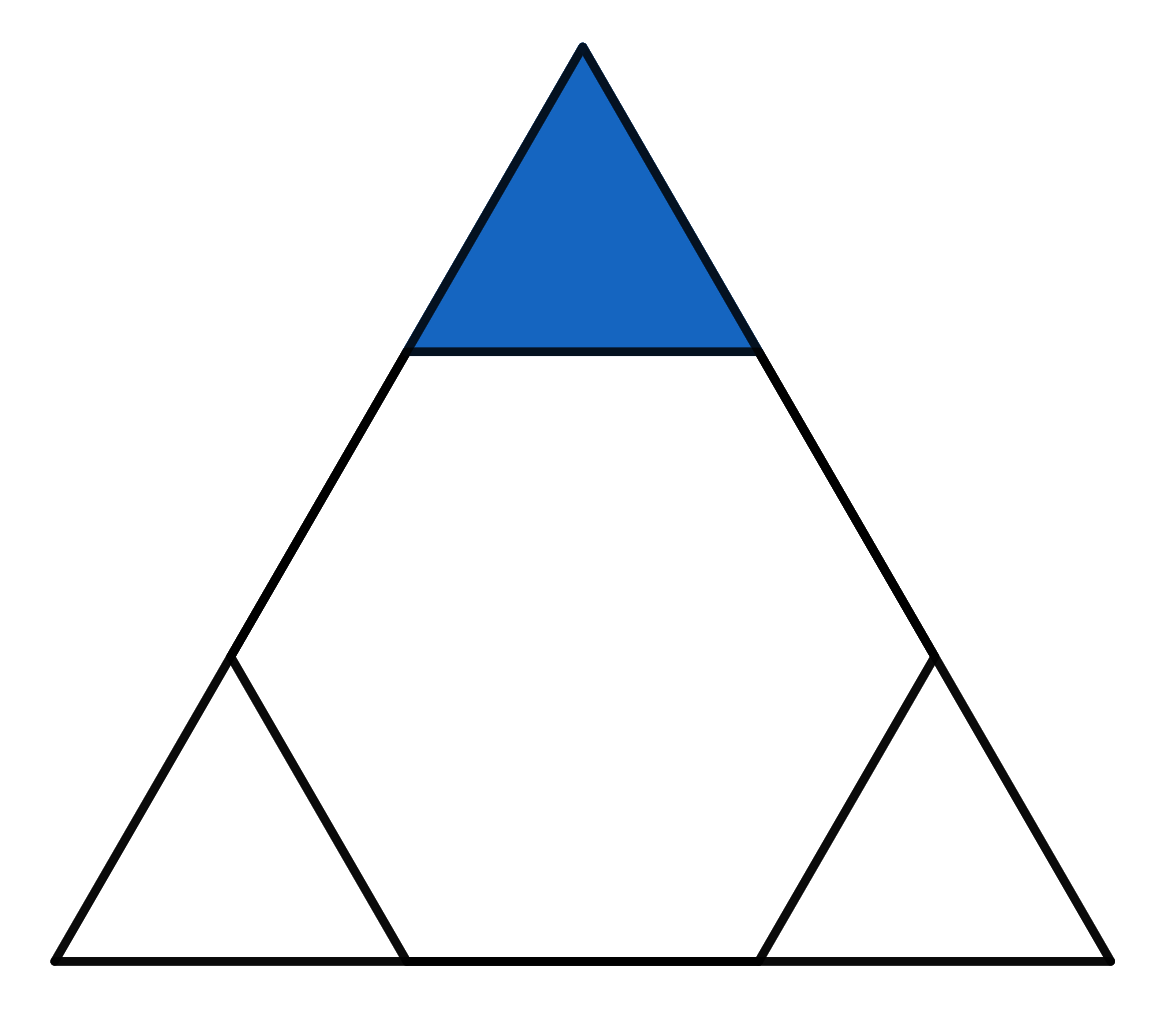

The triangle visible in the picture is equilateral. The hexagon inside is a regular hexagon. If the area of the whole big triangle is \(18\), find the area of the small blue triangle.

What has a greater value: \(300!\) or \(100^{300}\)?