Problems

Let \(m\) and \(n\) be positive integers. What positive integers can be written as \(m+n+\gcd(m,n)+\text{lcm}(m,n)\), for some \(m\) and \(n\)?

Let \(n\ge r\) be positive integers. What is \(F_n^2-F_{n-r}F_{n+r}\) in terms of \(F_r\)?

On the questioners’ planet (where everyone can only ask questions. Cricks can only ask questions to which the answer is yes, and Goops can only ask questions to which the answer is no), you meet 4 alien mathematicians.

They’re called Alexander Grothendieck, Bernhard Riemann, Claire

Voisin and Daniel Kan (you may like to shorten their names to \(A\), \(B\), \(C\)

and \(D\)).

Alexander asks the following question “Am I the kind who could ask

whether Bernhard could ask whether Claire could ask whether Daniel is a

Goop?"

Amongst the final three (that is, Bernhard, Claire and Daniel), are there an even or an odd number of Goops?

Four different digits are given. We use each of them exactly once to construct the largest possible four-digit number. We also use each of them exactly once to construct the smallest possible four-digit number which does not start with \(0\). If the sum of these two numbers is \(10477\), what are the given digits?

Have you wondered if \(F_{-5}\) is possible? Here is how we can extend the Fibonacci sequence to the negative indices. The relation \(F_{n+1} = F_n + F_{n-1}\) can be rewritten as \(F_{n-1} = F_{n+1} - F_n\). We can simply define the Fibonacci sequence with negative indices with this formula. For example, \(F_{-1} = F_1 - F_0 = 1 - 0 = 1\).

Write out \(F_{-1}, F_{-2},\dots,F_{-10}\). What do you notice about the Fibonacci sequence with negative indices?

On the questioners’ planet, there are two types of aliens, Cricks and Goops. These aliens can only ask questions. Cricks can only ask questions to which the answer is yes, Goops can only ask questions to which the answer is no.

There are 19 aliens standing in a circle. Each of them asks the following question “Do I have a Crick standing next to me on both sides?" Then one of them asks you in private “Is 57 a prime number?" How many Cricks were actually in the circle?

Suppose that \(n\) is a natural number and \(p\) is a prime number. How many numbers are there less than \(p^n\) that are relatively prime to \(p^n\)?

Two players are playing a game with a heap of \(100\) rocks, and they take turns removing rocks from the heap. The rules are the following: the first player takes one rock, the second can take either one or two rocks, then the first player can take one, two or three rocks, then the second can take \(1\), \(2\), \(3\) or \(4\) rocks from the pile and so on. That is, on each turn, the players have one more option for the number of rocks that they can take. The one who takes the last rock wins. Who has the winning strategy?

Find the minimal natural number \(n>1\) such that \(n^6 - 2n^5 - n^4 + 4n^3 - n^2 - 2n +1\) is divisible by \(2025\).

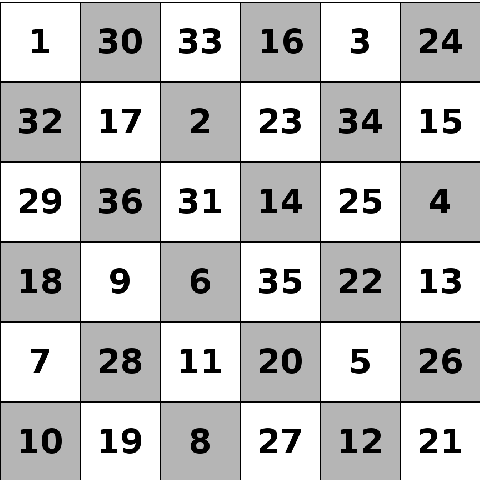

In chess, knights can move one square in one direction and two squares in a perpendicular direction. This is often seen as an ‘L’ shape on a regular chessboard. A closed knight’s tour is a path where the knight visits every square on the board exactly once, and can get to the first square from the last square.

This is a closed knight’s tour on a \(6\times6\) chessboard.

Can you draw a closed knight’s tour on a \(4\times4\) torus? That is, a \(4\times4\) square with both pairs of opposite sides identified in the same direction, like the diagram below.