Problems

You might want to know what day of the week your birthday is this

year. Mathematician John Conway invented an algorithm called the

‘Doomsday Rule’ to determine which day of the week a particular date

falls on. It works by finding the ‘anchor day’ for the year that you’re

working in. For \(2025\), the anchor

day is Friday. Certain days in the calendar always fall on the anchor

day. Some memorable ones are the following:

‘\(0\)’ of March - which is \(29\)th February in a leap year, and \(28\)th February otherwise.

\(4\)th April, \(6\)th June, \(8\)th August, \(10\)th October and \(12\)th December. These are easier to remember as \(4/4\), \(6/6\), \(8/8\), \(10/10\) and \(12/12\).

\(9\)th May, \(11\)th July, \(5\)th September and \(7\)th November. These are easier to see as

\(9/5\), \(11/7\), \(5/9\) and \(7/11\). A mnemonic for them is “9-5 at the

7-11".

Then find the nearest one of these dates to the date that you’re looking

for and find remainders.

For example, \(\pi\) day, (\(14\)th March, which is written \(3/14\) in American date notation. It’s also Albert Einstein’s birthday) is exactly \(14\) days after ‘\(0\)’th March, so is the same day of the week - Friday in \(2025\).

What day of the week will \(25\)th December be in \(2025\)?

\(6\) friends get together for a game of three versus three basketball. In how many ways can they be split into two teams? The order of the two teams doesn’t matter, and the order within the teams doesn’t matter.

That is, we count A,B,C vs. D,E,F as the same splitting as F,D,E vs A,C,B.

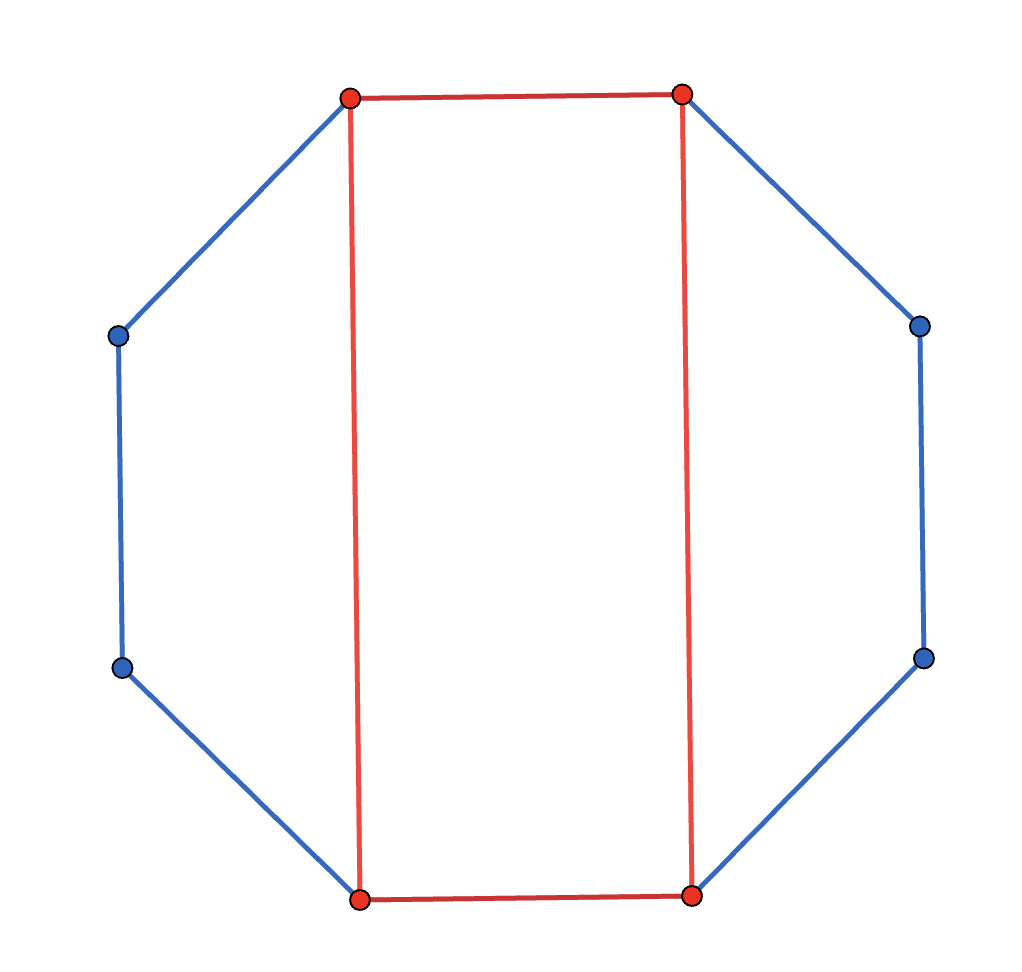

Below is a regular octagon. Given that its side length is \(1\), what’s the difference between the area of the red rectangle and the rest of the octagon?

\(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) are all integers. We’re told that \[\begin{align} x^3yz&=6\\ xy^3z&=24\\ xyz^3&=54. \end{align}\] What’s \(xyz\)?

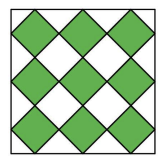

In the diagram, all the small squares are of the same size. What fraction of the large square is shaded?

The letters \(O\), \(P\), \(S\) and \(T\) represent different digits from \(1\) to \(9\). The same letters correspond to the same digits, while different letters correspond to different digits.

Find \(O+P+S+T\), given that \(SPOT+POTS=15,279\).

Picasso colours every point on the circumference of a circle red or blue. Is he guaranteed to create an equilateral triangle all of whose vertices are the same colour?

Let \(A\), \(B\), \(C\), \(D\), \(E\) be five different points on the circumference of a circle in that (cyclic) order. Let \(F\) be the intersection of chords \(BD\) and \(CE\). Show that if \(AB=AE=AF\) then lines \(AF\) and \(CD\) are perpendicular.

Let \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\) be positive real numbers such that \(a+b+c=3\). Prove that \(a^a+b^b+c^c\ge3\).

David and Esther play the following game. Initially, there are three piles, each containing 1000 stones. The players take turns to make a move, with David going first. Each move consists of choosing one of the piles available, removing the unchosen pile(s) from the game, and then dividing the chosen pile into 2 or 3 non-empty piles. A player loses the game if they are unable to make a move. Prove that Esther can always win the game, no matter how David plays.