Problems

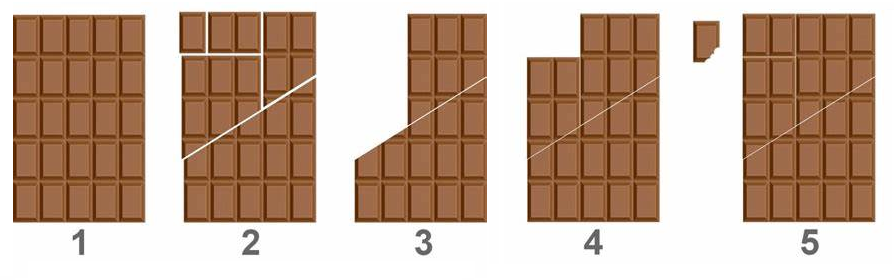

Eleven people were waiting in line in the rain, each holding an umbrella. They stood closely together, so that the umbrellas of the neighbouring people were touching (see the figure)

The rain stopped and everyone closed their umbrellas. They then shuffled closer, keeping a distance of \(50\) cm between neighbours. What is the ratio of the old queue length to the new queue length? People can be considered points, and umbrellas are circles with a radius of \(50\) cm.

Cut a square into five triangles in such a way that the area of one of these triangles is equal to the sum of the area of other four triangles.

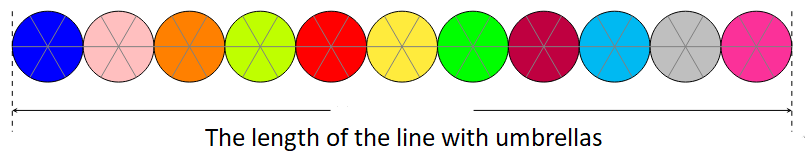

A circular triangle is a triangle in which the sides are arcs of

circles. Below is a circular triangle in which the sides are arcs of

circles centered at the vertices opposite to the sides.

Draw how Robinson Crusoe should put pegs and ropes to tie his goat in order for the goat to graze grass in the shape of the circular triangle.

In a box there are \(20\) cards of different colours: some red, some blue and some yellow. Yellow cards outnumber red ones and there are six times as many yellow cards as blue cards. We draw some cards from the box without looking. What is the minimum number we need to draw to guarantee a red card among them?

There are two piles of rocks, \(10\) rocks in each pile. Fred and George play a game, taking the rocks away. They are allowed to take any number of rocks only from one pile per turn. The one who has nothing to take loses. If Fred starts, who has the winning strategy?

Theorem: If we mark \(n\) points on

a circle and connect each point to every other point by a straight line,

the lines divide the interior of the circle is into is \(2n-1\) regions.

"Proof": First, let’s have a look at the smallest natural numbers.

When \(n=1\) there is one region (the whole disc).

When \(n=2\) there are two regions (two half-discs).

When \(n=3\) there are \(4\) regions (three lune-like regions and one triangle in the middle).

When \(n=4\) there are \(8\) regions, and if you’re still not convinced then try \(n=5\) and you’ll find \(16\) regions if you count carefully.

Our proof in general will be by induction on \(n\). Assuming the theorem is true for \(n\) points, consider a circle with \(n+1\) points on it. Connecting \(n\) of them together in pairs produces \(2n-1\) regions in the disc, and then connecting the remaining point to all the others will divide the previous regions into two parts, thereby giving us \(2\times (2n-1)=2n\) regions.

Let’s "prove" that the number \(1\) is a multiple of \(3\). We will use the symbol \(\equiv\) to denote "congruent modulo \(3\)". Thus, what we need to prove is that \(1\equiv 0\) modulo \(3\). Let’s see: \(1\equiv 4\) modulo \(3\) means that \(2^1\equiv 2^4\) modulo \(3\), thus \(2\equiv 16\) modulo \(3\), however \(16\) gives the remainder \(1\) after division by \(3\), thus we get \(2\equiv 1\) modulo \(3\), next \(2-1\equiv 1-1\) modulo \(3\), and thus \(1\equiv 0\) modulo \(3\). Which means that \(1\) is divisible by \(3\).

Recall that \((n+1)^2=n^2+2n+1\). Subtracting \(2n+1\) from both sides gives \((n+1)^2-(2n+1)=n^2\). Now subtract \(n(2n+1)\) from both sides to obtain \((n+1)^2-(2n+1)-n(2n+1)=n^2-n(2n+1)\). Notice that the left-hand side can be rewritten as \((n+1)^2-(n+1)(2n+1)\), so we have \((n+1)^2-(n+1)(2n+1)=n^2-n(2n+1)\).

Next, add \(\frac{(2n+1)^2}{4}\) to both sides. This allows us to complete the square on each side, giving \(((n+1)-\frac{2n+1}{2})^2=(n-\frac{2n+1}{2})^2\).

Taking square roots of both sides leads to \((n+1)-\frac{2n+1}{2}=n-\frac{2n+1}{2}\). Adding \(\frac{2n+1}{2}\) to both sides produces \(n+1=n\), which simplifies to \(1=0\).

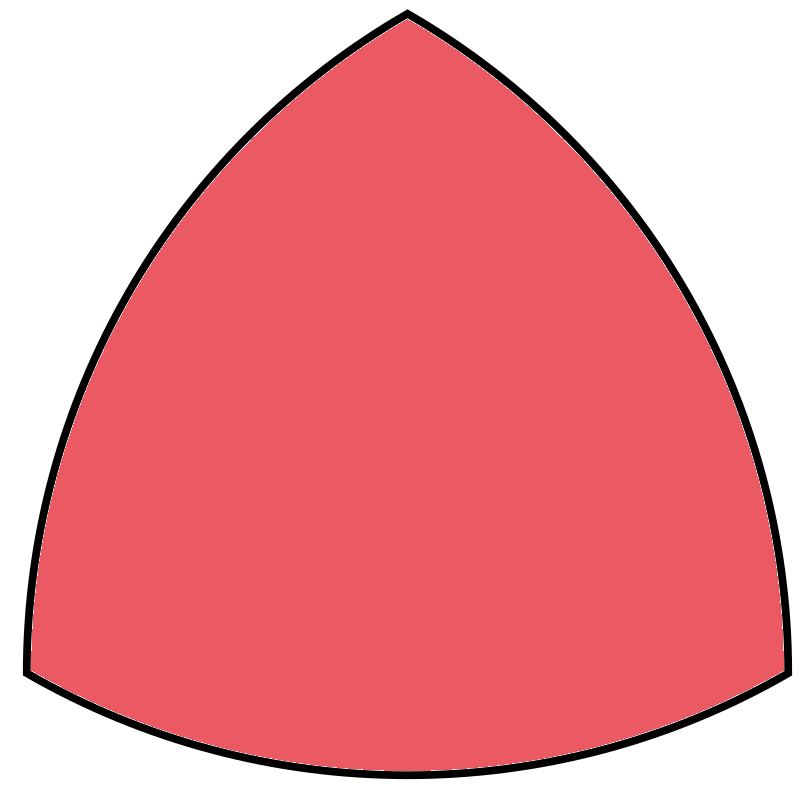

Look at the diagram below, which shows how to rearrange the pieces forming the first triangle.

The shape seems unchanged, yet after looking more closely, we see that

the second picture appears to contain one extra square of area. How can

this be?

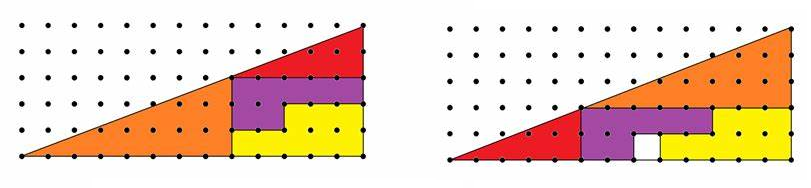

This problem is often called "The infinite chocolate bar". Depicted

below is a way to get one more piece of chocolate from the \(5\times 6\) chocolate bar. Do you see where

is it wrong?