Problems

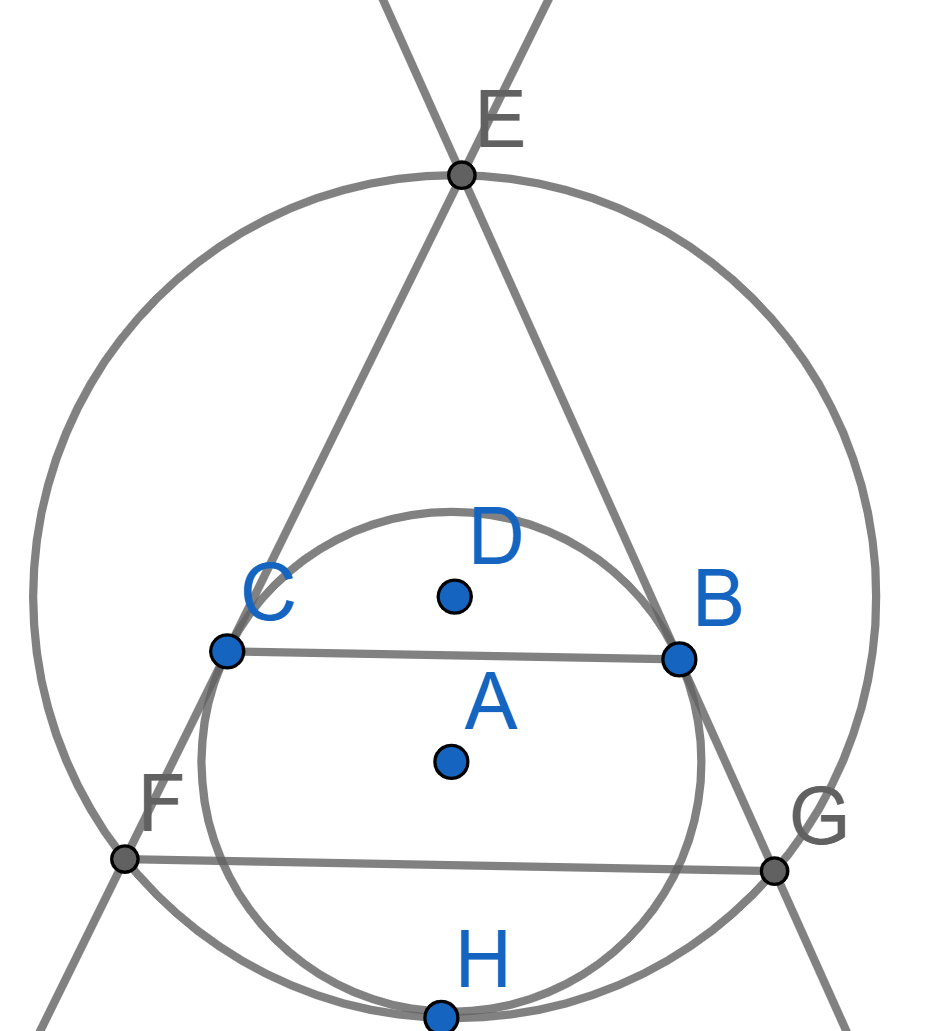

The triangle \(EFG\) is isosceles with \(EF=EG\). A circle with center \(A\) is tangent to the sides \(EF\) and \(EG\) at the points \(C\) and \(B\) respectively. It is also tangent to the circle circumscribed around the triangle \(EFG\) at the point \(H\). Prove that the midpoint of the segment \(BC\) is the center of the circle inscribed into the triangle \(EFG\).

Prove that under a homothety transformation, a polygon is transformed into a similar polygon.

Hint: to show this, why is it enough for you to show that homothety preserves angles and ratios?

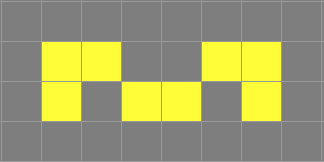

In the Game of Life, each cell in a grid is either alive or dead (in the diagram, yellow cells are alive). At each step, a live cell stays alive only if it has \(2\) or \(3\) live neighbours, otherwise it dies; a dead cell becomes alive only if it has exactly \(3\) live neighbours. A still-life is a pattern that does not change after any number of steps. Show that the following pattern cannot be turned into a still-life by only changing dead cells into alive cells.

Is it possible to arrange \(10\) numbers in a row such that:

The sum of any \(4\) consecutive numbers is positive.

The sum of any \(5\) consecutive numbers is positive.

The sum of any \(7\) consecutive numbers is negative?

In how many different ways can you place \(12\) chips in the squares of a \(4\times 4\) board so that

there is at most one chip in each square, and

every row and every column contains exactly three chips?

On a TV screen the number \(1\) appears. Every minute that passes by, the number that is currently on the screen increases by the sum of its digits. For example: if at some point the number \(12\) appears on the screen, the next number will be \(12+(1+2)=15.\) Will the number \(123456\) ever appear on the screen?

Seven vertices of a cube are labelled with the number \(0\), and the remaining vertex is labelled with \(1\). You are allowed to repeat the following move: choose an edge of the cube and increase by \(1\) the numbers at both ends of that edge.

Is it possible to reach eight numbers that are all divisible by three?

Each number on the number line (not only whole numbers!) is painted black \((B)\) or white \((W)\). Is it always possible, regardless of how the number line is painted, to find a line segment such that both its endpoints and its middle point are painted with the same colour?

A book club with 37 members is reading the following books: “Brave New World", “Dracula" and “Flatland". Each member chose one of the books, though some people chose more than one book. We know that:

23 people chose “Brave New World";

18 people chose “Dracula";

26 people chose “Flatland";

7 people chose all three books.

How many people chose at least two books?

Jan wants to paint a map with \(95\) countries on it, where only one colour can be used for each country. He has \(33\) different colours to paint with and he must use each of yellow, blue, green, purple and red at least once. How many ways of painting the map are there?