Problems

Which of the two following numbers is larger: \(31^{11}\) or \(17^{14}\)?

There are \(2026\) people at a big party. Some pairs of people are friends (nobody is friends with themselves, and friendship goes both ways). Starting one minute after midnight, the host begins sending people home in a strange way.

After 1 minute, anyone with no friends at the party leaves. After 2 minutes, anyone with exactly one friend currently in the party leaves. After 3 minutes, anyone with exactly two friends currently in the party leaves, and so on.

(Important: at each minute, everyone checks their number of friends at the same time, and then all the people who qualify leave together.)

Show that after \(2026\) minutes have passed, at least two people will have left the party.

Zippity the robot speaks a language of \(n\) words which can be written with \(0\)s and \(1\)s. In this language, no word appears as the first several digits of another word. For example: if “\(1001\)” is a word, then “\(100101\)” can’t be a word. Show that if \(\ell_1,\cdots, \ell_n\) are the lengths of each word (i.e: the number of digits), then \[\frac{1}{2^{\ell_1}}+\frac{1}{2^{\ell_2}}+\cdots + \frac{1}{2^{\ell_n}}\leq 1.\]

You have a \(5\)-liter bucket and a \(3\)-liter bucket, along with an unlimited supply of water.

You are allowed to do only these moves:

fill a bucket completely from the water supply,

empty a bucket completely,

pour water from one bucket into the other until either the first bucket is empty or the second bucket is full.

Find two different ways to end up with exactly \(4\) liters of water (Adding extra steps that don’t change the situation, like filling a bucket and then immediately emptying it again, does not count as finding a new way).

Prove that under a homothety transformation, a circle is transformed into another circle. Consider all possible cases of \(k\): \(k<0, 0<k \leq 1, 1\leq k\).

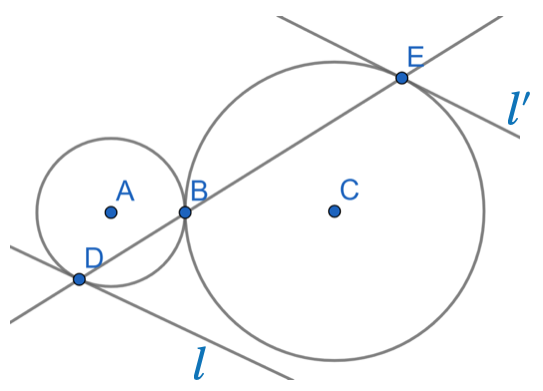

Two circles with centres \(A\) and \(C\) are tangent at the point \(B\). The segment \(DE\) passes through the point \(B\). Prove that the tangent lines \(l\) and \(l'\) passing through the points \(D\) and \(E\) respectively, are parallel.

Let \(ABCD\) be a square, a point

\(I\) a random point on the plane.

Consider the four points, symmetric to \(I\) with respect to the midpoints of \(AB, BC, CD, AD\). Prove that these new four

points are vertices of a square.

In case you need a refresher, we say that a point \(X'\) is symmetric to a point \(X\) with respect to a point \(M\) if \(M\) is the midpoint of the segment \(XX'\).

Replace the stars with positive whole numbers so that \[\frac{1}{*}+\frac{1}{*}=\frac{7}{48}.\]

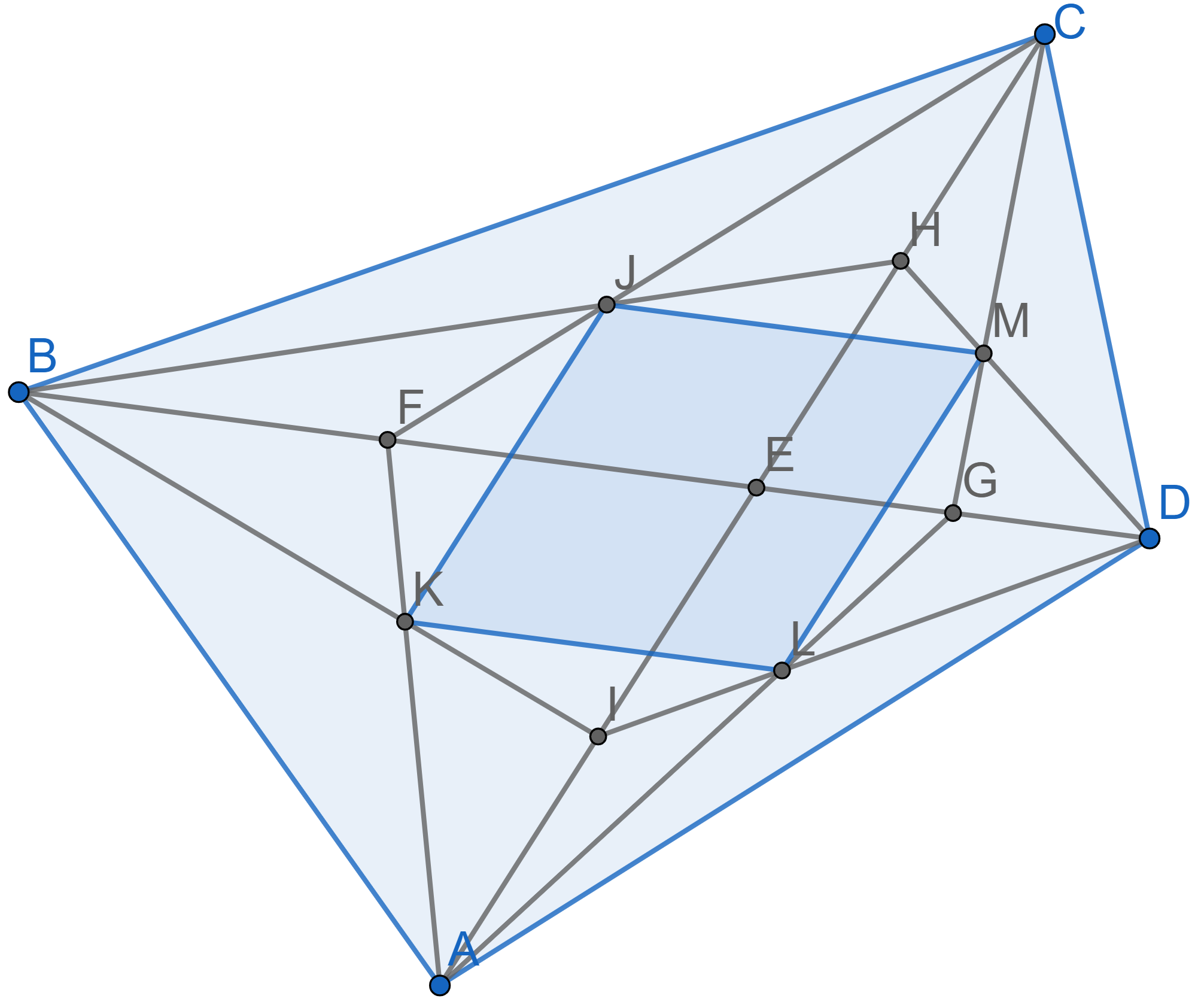

Let \(ABCD\) be a quadrilateral whose diagonals intersect at a point \(E\).

Consider the four triangles \(ABE\), \(BCE\), \(CDE\), and \(ADE\). For each triangle, draw its medians, and let \(K\), \(J\), \(M\), and \(L\) be the points where the medians intersect in the triangles \(ABE\), \(BCE\), \(CDE\), and \(ADE\), respectively.

Prove that the quadrilateral \(KJML\) is a parallelogram.

You may wish to use the fact that the point of intersection of the medians of any triangle divides each median in the ratio \(2:1\), counting from the vertex, but if you use this fact, you should prove it.

At the Oscar Awards 2025, 5 films were nominated for Best Production Design and 5 films were nominated for Best Cinematography. In fact, 3 films were nominated for both categories. What is the total number of films nominated for these two categories?