Problems

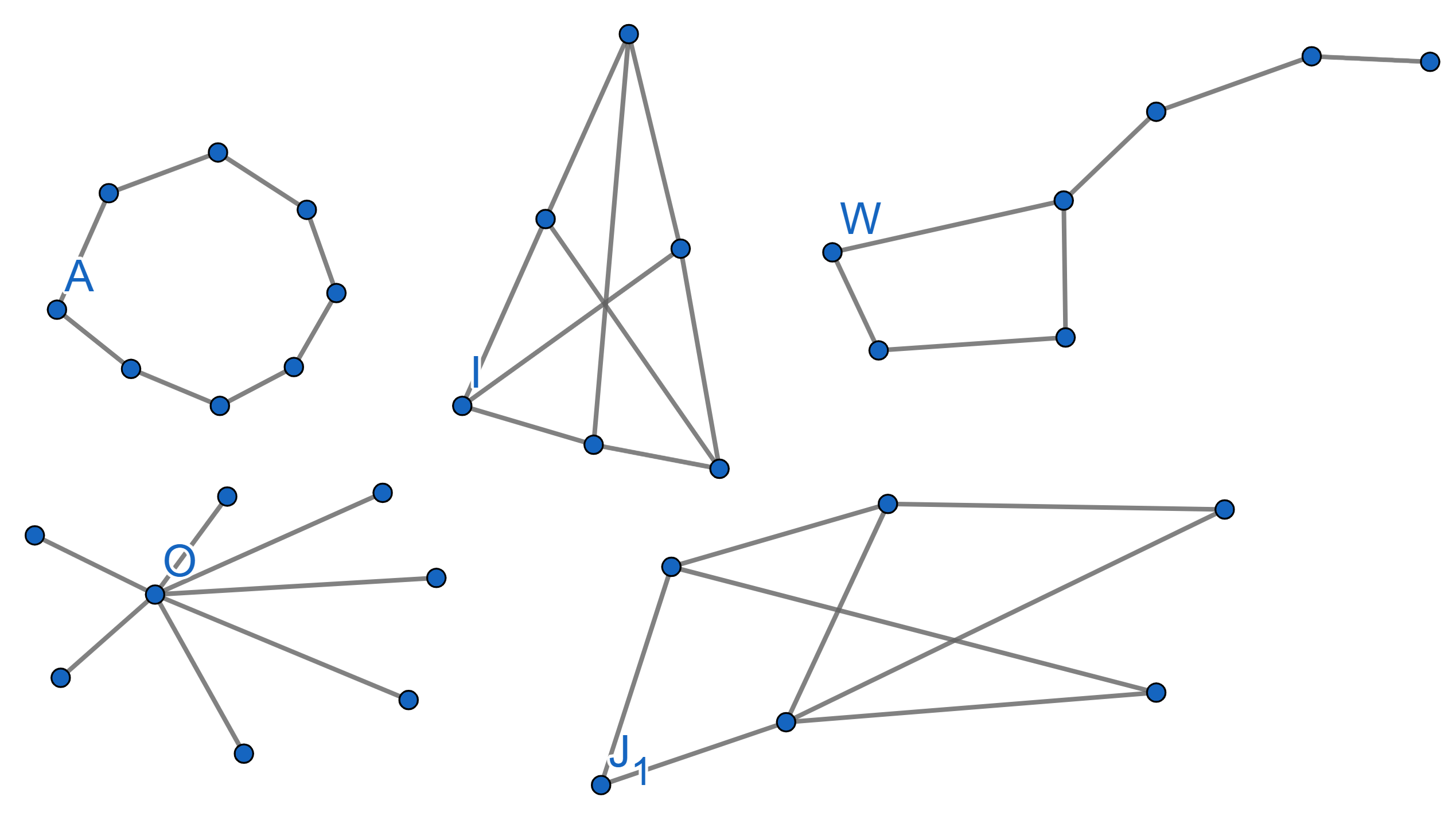

A graph is called Bipartite if it is possible to split all its vertices into two groups in such a way that there are no edges connecting vertices from the same group. Find out whic of the following graphs are bipartite and which are not:

Show that a bipartite graph with \(n\) vertices cannot have more than \(\frac{n^2}{4}\) edges.

In a graph \(G\), we call a

matching any choice of edges in \(G\) in such a way that all vertices have

only one edge among chosen connected to them. A perfect

matching is a matching which is arranged on all vertices of the

graph.

Let \(G\) be a graph with \(2n\) vertices and all the vertices have

degree at least \(n\) (the number of

edges exiting the vertex). Prove that one can choose a perfect matching

in \(G\).

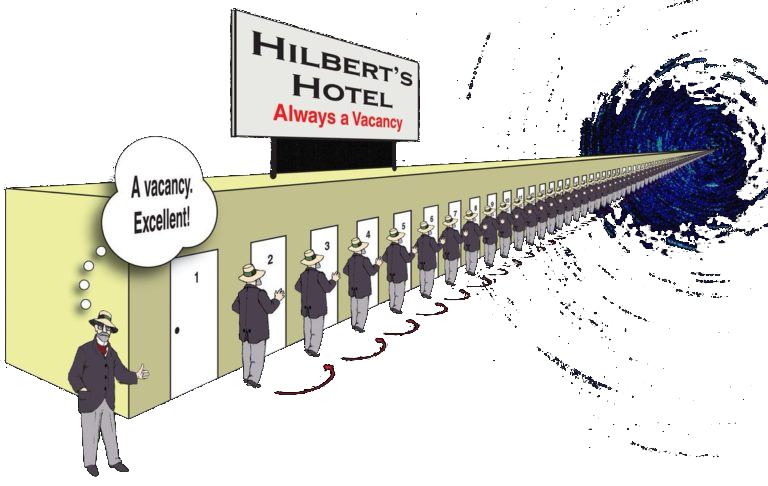

A new customer comes to the hotel and wants a room. It happened today that all the rooms are occupied. What should you do?

Now imagine you got \(10\) new guests arriving to the completely full hotel. What should you do now?

The next day you have even harder situation: to the hotel, where all the rooms are occupied arrives a bus with infinitely many new customers. In the bus all the seats have numbers \(1,2,3...\) corresponding to all natural numbers. How to deal with this one?

Imagine you have \(2\) new guests arriving to the full hotel. How do you accommodate them?

What would you do about \(10000\) new guests arriving to the full hotel?

Imagine you have now a general finite number of new guests arriving to the full hotel. What do you do?

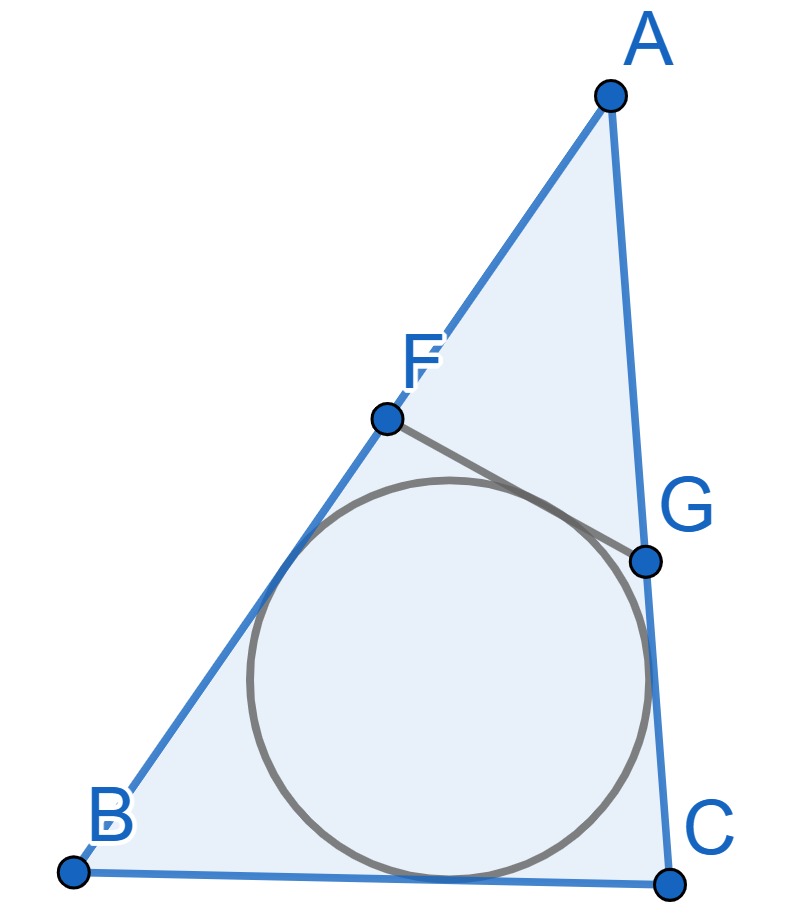

A circle is inscribed into the triangle \(ABC\) with sides \(BC=6, AC=10\) and \(AB= 12\). A line tangent to the circle intersects two longer sides of the triangle \(AB\) and \(AC\) at the points \(F\) and \(G\) respectively. Find the perimeter of the triangle \(AFG\).