Problems

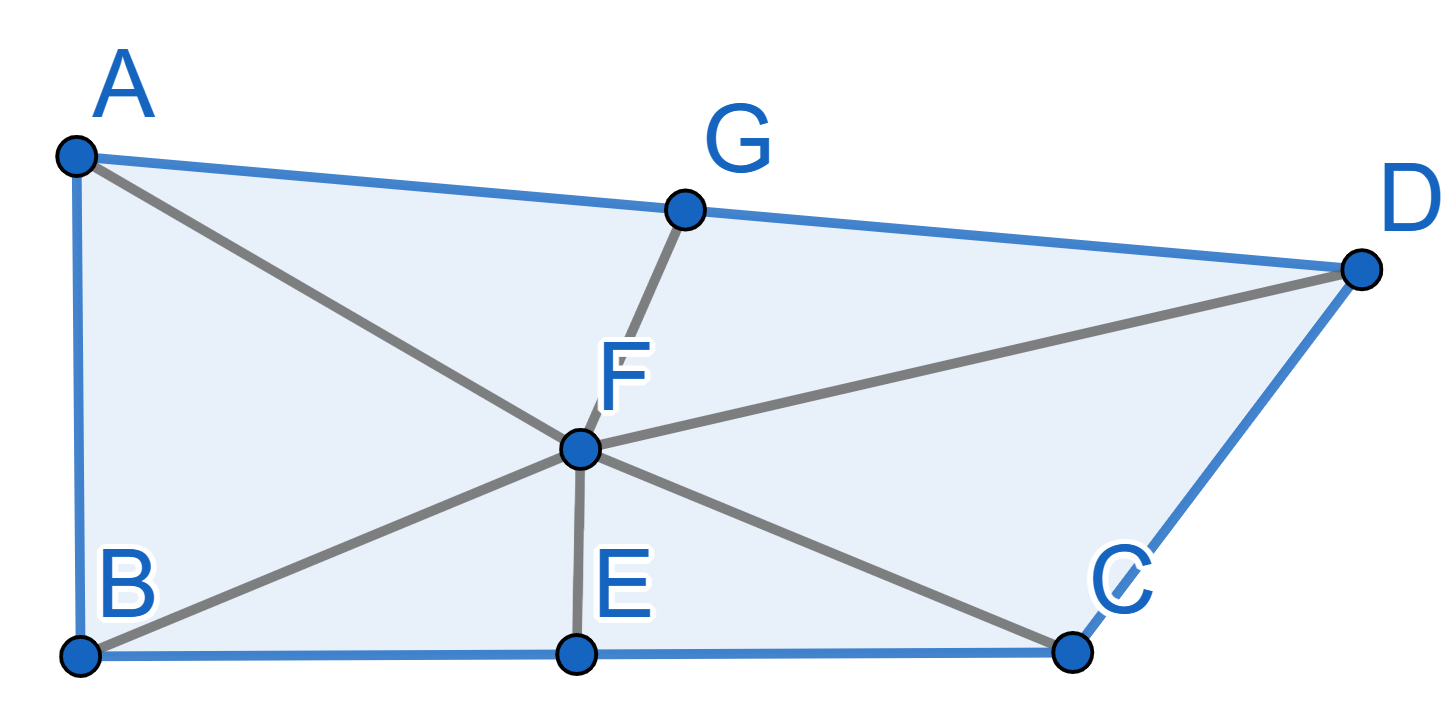

Let’s prove that any \(90^{\circ}\)

angle is equal to any angle larger than \(90^{\circ}\). On the diagram

We have the angle \(\angle ABC =

90^{\circ}\) and angle \(\angle BCD>

90^{\circ}\). We can choose a point \(D\) in such a way that the segments \(AB\) and \(CD\) are equal. Now find middles \(E\) and \(G\) of the segments \(BC\) and \(AD\) respectively and draw lines \(EF\) and \(FG\) perpendicular to \(BC\) and \(AD\).

Since \(EF\) is the middle

perpendicular to \(BC\) the triangles

\(BEF\) and \(CEF\) are equal which implies the equality

of segments \(BF\) and \(CF\) and of angles \(\angle EBF = \angle ECF\), the same about

the segments \(AF=FD\). By condition we

have \(AB=CD\), thus the triangles

\(ABF\) and \(CDF\) are equal, thus \(\angle ABF = \angle DCF\). But then we have

\[\angle ABE = \angle ABF + \angle FBE =

\angle DCF + \angle FCE = \angle DCE.\]

Let’s prove that \(1=2\). Take a number \(a\) and suppose \(b=a\). After multiplying both sides we have \(a^2=ab\). Subtract \(b^2\) from both sides to get \(a^2-b^2=ab-b^2\). The left hand side is a difference of two squares so \((a-b)(a+b)=b(a-b)\). We can cancel out \(a-b\) and obtain that \(a+b=b\). But remember from the start that \(a=b\), so substituting \(a\) for \(b\) we see that \(2b=b\), dividing by \(b\) we see that \(2=1\).

Let’s prove that \(1\) is the smallest positive real number: Assume the contrary and let \(x\) be the smallest positive real number. If \(x>1\) then \(1\) is smaller, thus \(x\) is not the smallest. If \(x<1,\) then \(\frac{x}{2}<x\) so \(x\) can not be the smallest either. Then \(x\) can only be equal to \(1\).

Nick writes the numbers \(1,2,\dots,33\), each exactly once, at the vertices of a polygon with \(33\) sides, in some order.

For each side of the polygon, his little sister Hannah writes down the sum of the two numbers at its ends. In total she writes down \(33\) numbers, one for each side.

It turns out that when read in order around the polygon, these \(33\) sums are \(33\) consecutive whole numbers.

Can you find an arrangement of the numbers written by Nick that makes this happen?

Is it possible to arrange the numbers \(1,\, 2,\, ...,\, 50\) at the vertices and middles of the sides of a regular \(25\)-gon so that the sum of the three numbers at the ends and in the middle of each side is the same for all sides?

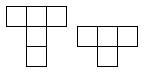

Draw a shape that can both be cut into 4 copies of the figure on the left or alternatively into 5 copies of the figure on the right. (the figures can be rotated).

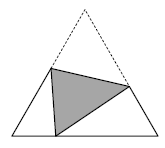

A equilateral triangle made of paper bends in a straight line so that

one of the vertices falls on the opposite side as shown on the picture.

Show that the corresponding angles of the two white triangles are

equal.

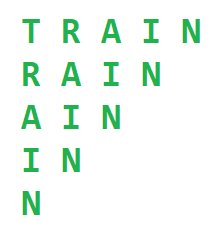

In how many ways can you read the word TRAIN from the picture below, starting from T and going either down or right at each step?

There are \(100\) people in a room. Each person knows at least \(67\) others. Show that there is a group of four people in this room that all know each other. We assume that if person \(A\) knows person \(B\) then person \(B\) also knows person \(A\).

The numbers \(a\) and \(b\) are integers and the number \(p \ge 3\) is prime. Suppose that \(a+b\) and \(a^2 +b^2\) are divisible by \(p\). Show that \(a^2 + b^2\) is divisible by \(p^2\).