Problems

There are \(33\) cities in the Republic of Farfarawayland. The delegation of senators wants to pick a new capital city. They want this city to be connected by roads to every other city in the Republic. They know for a fact that given any set of \(16\) cities, there will always be some city that is connected by roads to all those selected cities. Show that there exists a suitable candidate for the capital.

John drunk a \(\frac16\) of a full cup of black coffee and then filled the cup back up with milk. Then he drunk a third of what he had in the cup. Then, he refilled it back to full with milk again, and after that, drunk a half of the cup. Finally, he once again refilled the cup with milk and drunk everything he had. What did he drink more of - coffee or milk?

A round necklace contains \(45\) beads of two different colours: red and blue. Show that it is possible to find two beads of the same colour next to each other.

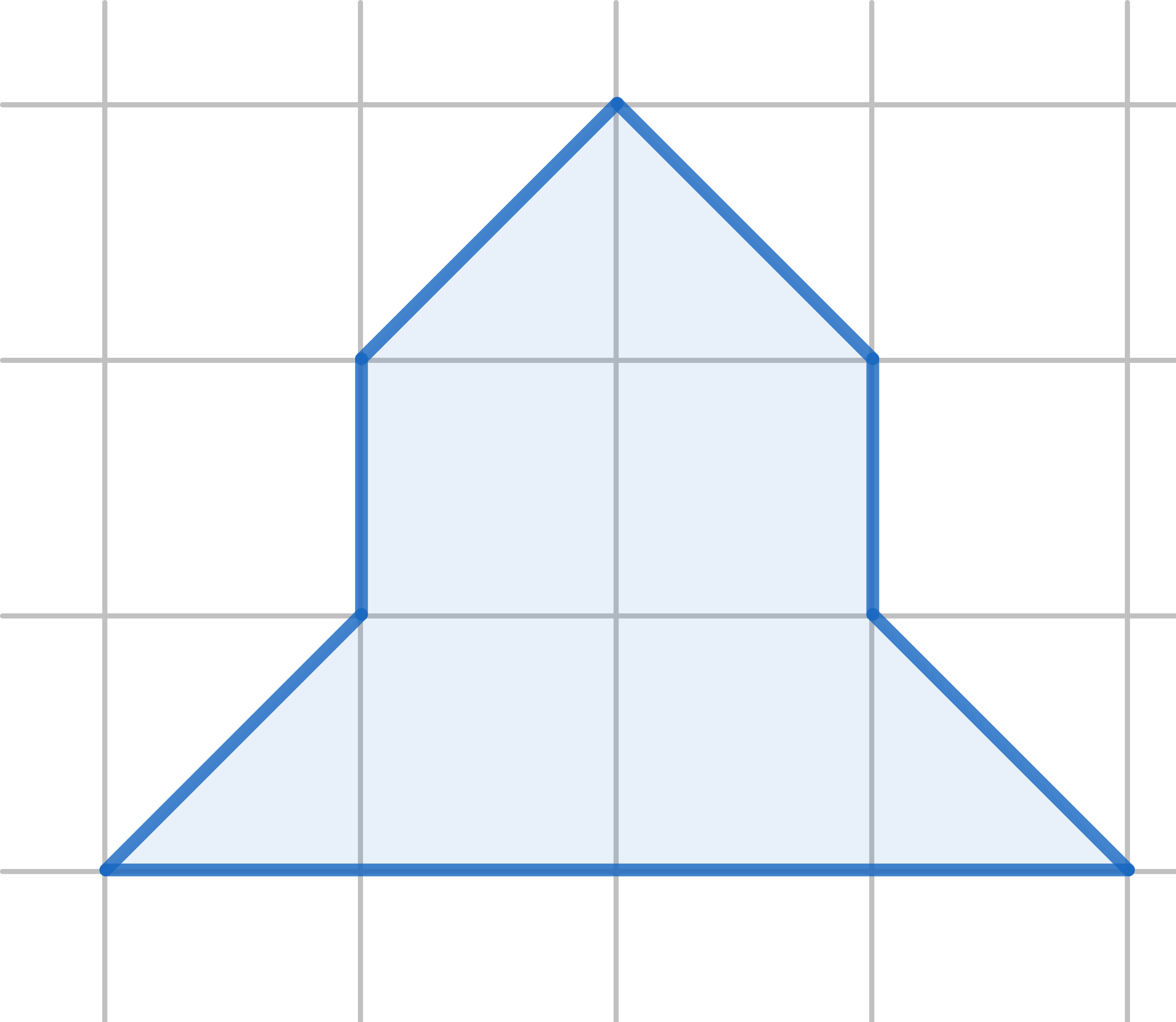

Cut this figure into \(4\) identical shapes. (Note: you have to use the entire shape. Rotations and reflections count as identical shapes)

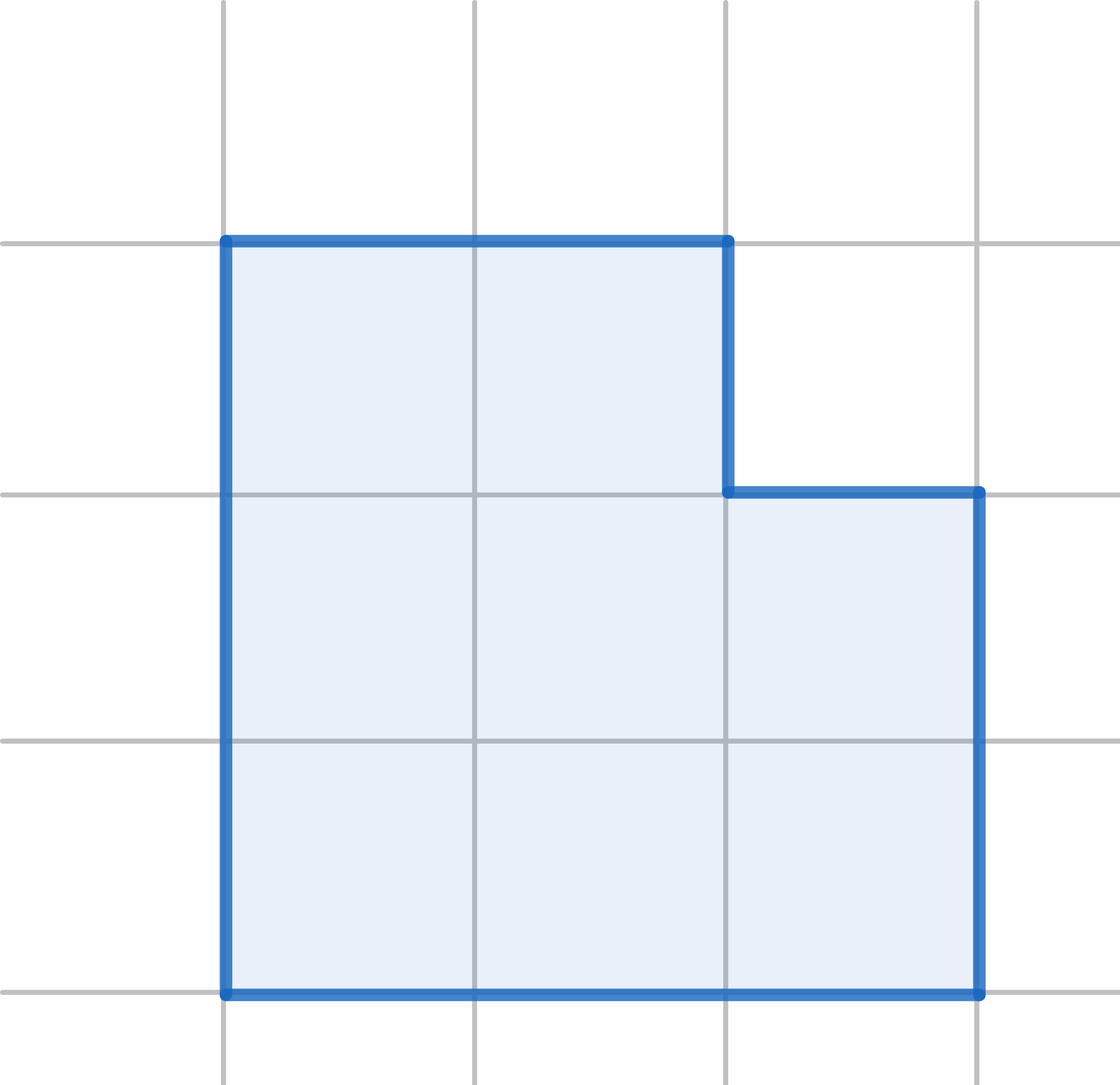

The diagram shows a \(3 \times 3\) square with one corner removed. Cut it into three pieces, not necessarily identical, which can be reassembled to make a square:

Find all possible non-zero digits \(A\) for which the following holds \((AA+AA+1) \times A = AAA\). (Recall \(AA\) means the two-digit number whose first and second digits are \(A\))

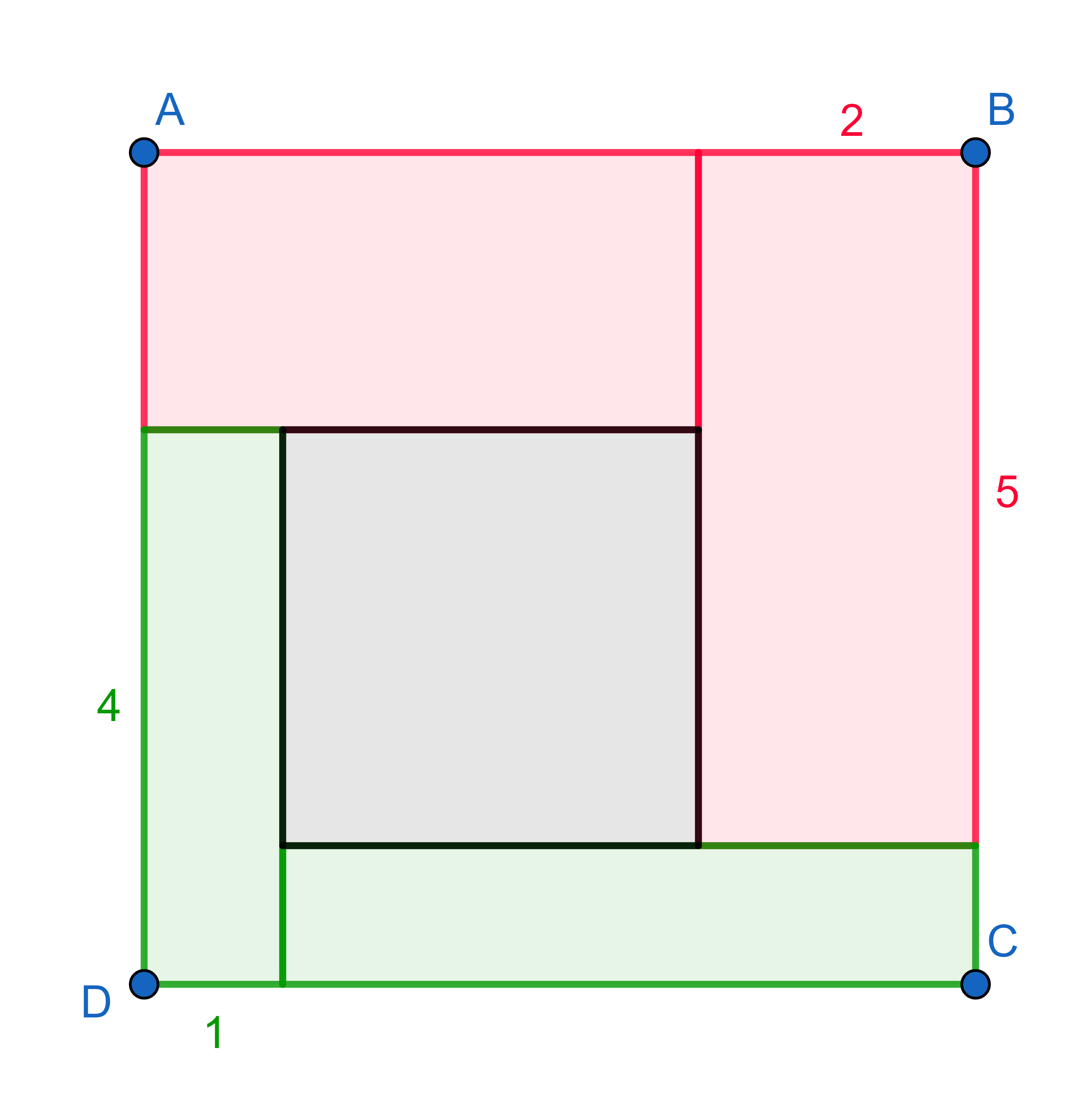

A square has been divided into \(4\) rectangles and a square. If the rectangle in the bottom left corner has dimensions \(1 \times 4\) and the one in the top right is \(2 \times 5\), what is the area of the small square in the middle?

There are \(25\) bugs sitting on the squares of a \(5 \times 5\) board, \(1\) at each square. When I clap my hands, each bug jumps to a square diagonally from where it was before. Show that after I clap my hands, at least \(5\) squares will be empty.

A polygon is called convex if every interior angle is less than \(180^\circ\), that is, the shape does not “bulge inwards”. In a convex quadrilateral \(ABCD\), all the triangles \(\triangle ABC\), \(\triangle BCD\), \(\triangle CDA\) and \(\triangle DAB\) have equal perimeters. Show that \(ABCD\) is a rectangle.

Find the last two digits of the number \[33333333333333333347^4 - 11111111111111111147^4\]