Problems

For any positive integer \(k\), the factorial \(k!\) is defined as a product of all integers between 1 and \(k\) inclusive: \(k! = k \times (k-1) \times ... \times 1\). What’s the remainder when \(2025!+2024!+2023!+...+3!+2!+1!\) is divided by \(8\)?

There are two imposters and seven crewmates on the rocket ‘Plus’. How many ways are there for the nine people to split into three groups of three, such that each group has at least two crewmates? The two imposters and seven crewmates are all distinguishable from each other, but we’re not concerned with the order of the three groups.

For example: \(\{I_1,C_1,C_2\}\), \(\{I_2,C_3,C_4\}\) and \(\{C_5,C_6,C_7\}\) is the same as \(\{C_3,C_4,I_2\}\), \(\{C_5,C_6,C_7\}\) and \(\{I_1,C_2,C_1\}\) but different from \(\{I_2,C_1,C_2\}\), \(\{I_1,C_3,C_4\}\) and \(\{C_5,C_6,C_7\}\).

Let \(n\) be a natural number, and let \(d(n)\) be the number of factors of \(n\). For example, the factors of \(6\) are \(1,2,3,6\), so \(d(6)=4\). Find all \(n\) such that \(d(n)+d(n+1)=5\).

King Hattius has three prisoners and gives them the following puzzle. He will put a randomly coloured hat on each of their heads: red, blue or green. He’ll then give them \(10\) seconds for them to each guess their own hat’s colour at the same time.

However! Each prisoner can only see the other two prisoners’ hats, not their own. There are no mirrors in the prison, and they are not allowed to take off their hat, nor talk, mouth, use sign-language, or otherwise communicate with the other two prisoners during those ten seconds.

Hattius tells them that he’ll release them all if at least one correctly guesses their hat’s colour. He gives them an hour to come up with a strategy - what should their strategy be?

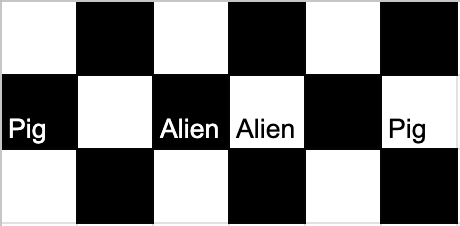

Two aliens want to abduct two humans, but aren’t paying attention, so instead run after pigs. They’re all on squares of a \(3\times6\) rectangle, as seen below. On the first move, the aliens move one square horizontally or vertically. Then on the second move, the pigs move horizontally or vertically. The third move is for the aliens, the fourth move is for the pigs, and so on. If an alien lands on a square with a pig on it, then they’ve succeeded. Show that no matter what the pigs do, they’re doomed.

In the diagram below, there are nine discs - each is black on one side, and white on the other side. Two have black face-up right now. Your task is to remove all of the discs by making a series of the following moves. Each move includes choosing a black disc, flipping over its neighbours\(^*\) and removing that black disc. Discs are ‘neighbours’ if they’re adjacent at the beginning - removing a disc creates a gap, so that at later stages, a disc may have two, one or even zero neighbours left. \[\circ\circ\circ\bullet\circ\circ\circ\circ\bullet\] Show that this task is impossible.

Draw the plane tiling with regular hexagons.

Let \(\sigma(n)\) be the sum of the divisors of \(n\). For example, \(\sigma(12)=1+2+3+4+6+12=28\). We use \(\gamma\) to denote the Euler-Mascheroni constant - one way to define this is as \(\gamma:=\lim_{n\to\infty}(\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{1}{n}-\log n)\).

Prove that \(\sigma(n)<e^{\gamma}n\log\log n\) for all integers \(n>5040\).

Let \(a\) and \(b\) be two different \(9\)-digit numbers. It is known that each one of them contains all of the digits \(1,2,...9\). Find the maximal value of \(\gcd(a,b)\).

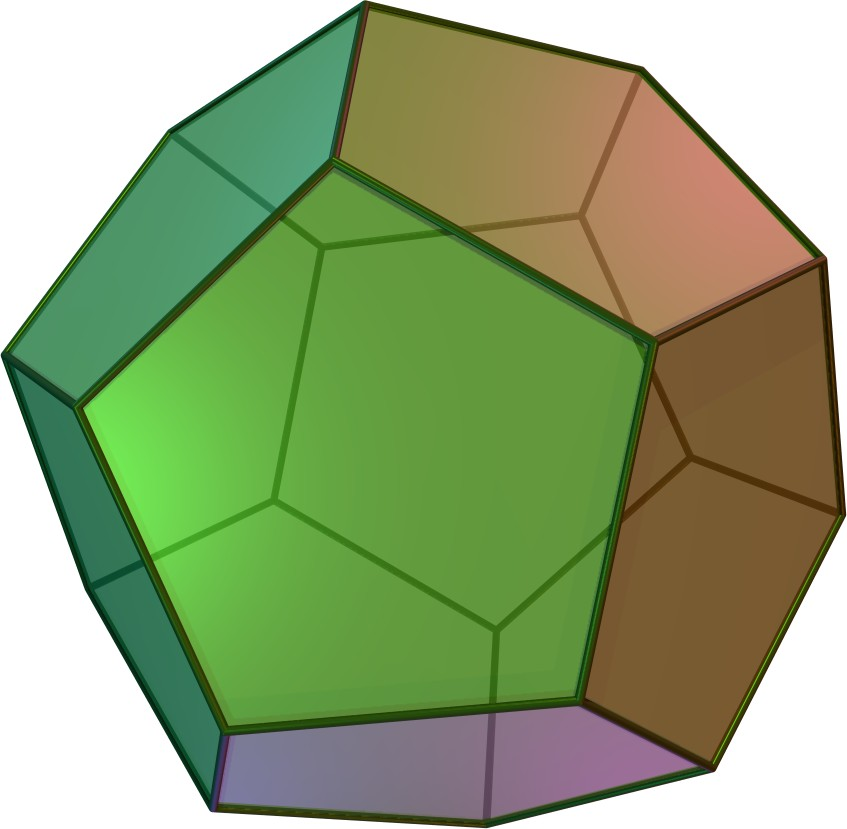

Take a regular dodecahedron as in the image. It has \(12\) regular pentagons as its faces, \(30\) edges, and \(20\) vertices. We can cut it with planes in various ways and the cut will be a polygon on a plane. Find out how many ways there are to cut a dodecahedron with a plane so that the polygon obtained is a regular hexagon.