Problems

There are \(25\) bugs sitting on the squares of a \(5 \times 5\) board, \(1\) at each square. When I clap my hands, each bug jumps to a square diagonally from where it was before. Show that after I clap my hands, at least \(5\) squares will be empty.

A polygon is called convex if every interior angle is less than \(180^\circ\), that is, the shape does not “bulge inwards”. In a convex quadrilateral \(ABCD\), all the triangles \(\triangle ABC\), \(\triangle BCD\), \(\triangle CDA\) and \(\triangle DAB\) have equal perimeters. Show that \(ABCD\) is a rectangle.

Find the last two digits of the number \[33333333333333333347^4 - 11111111111111111147^4\]

Replace all stars with ”+” or ”\(\times\)” signs so the equation holds: \[1*2*3*4*5*6=100\] Extra brackets may be added if necessary. Please write down the expression into the answer box.

In how many ways can one change \(\pounds 2\) into coins worth \(50\)p, \(20\)p and \(10\)p? One does not necessarily need to use all available coin types, i.e. having \(5\) coins of \(20\)p and \(10\) coins of \(10\)p is allowed.

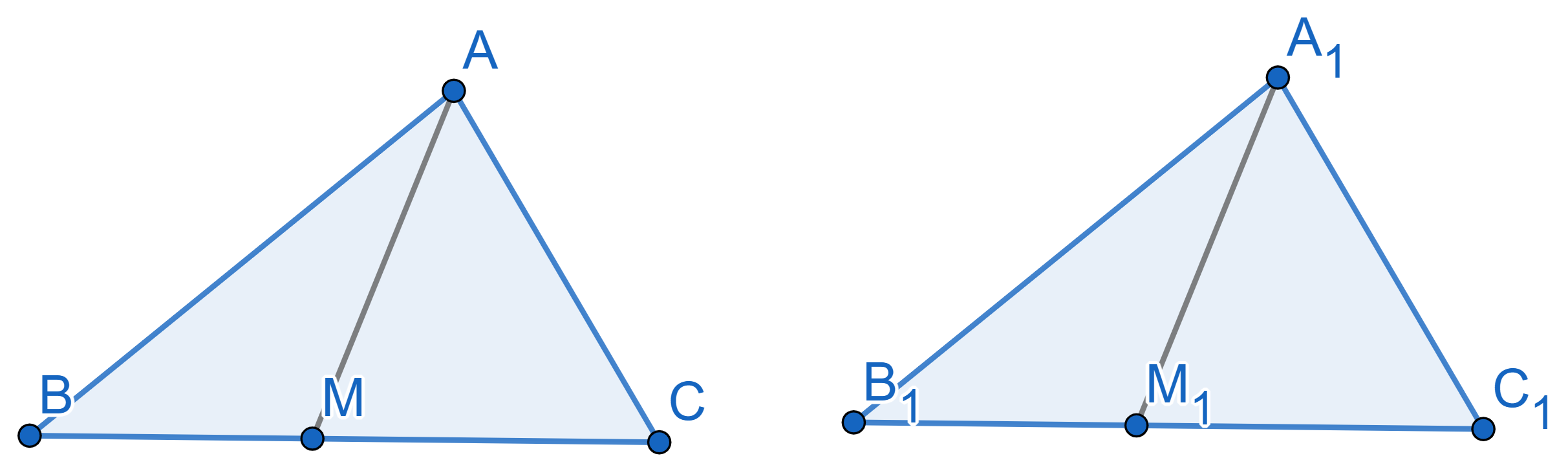

Consider two congruent triangles \(ABC\) and \(A_1B_1C_1\). We draw a point \(M\) on the side \(BC\) and a point \(M_1\) on the side \(B_1C_1\) such that the ratio of lengths

\(BM:MC\) is equal to the ratio of

lengths \(B_1M_1:M_1C_1\). Prove that

\(AM = A_1M_1\).

We call a median the segment from the vertex of a triangle to the midpoint of the opposite side. Prove that in two congruent triangles, the corresponding medians are of equal length.

We call a bisector the segment from the vertex of a triangle to the opposite side which divides in half the angle next to the starting vertex. Prove that in two congruent triangles, the corresponding bisectors are of equal length.

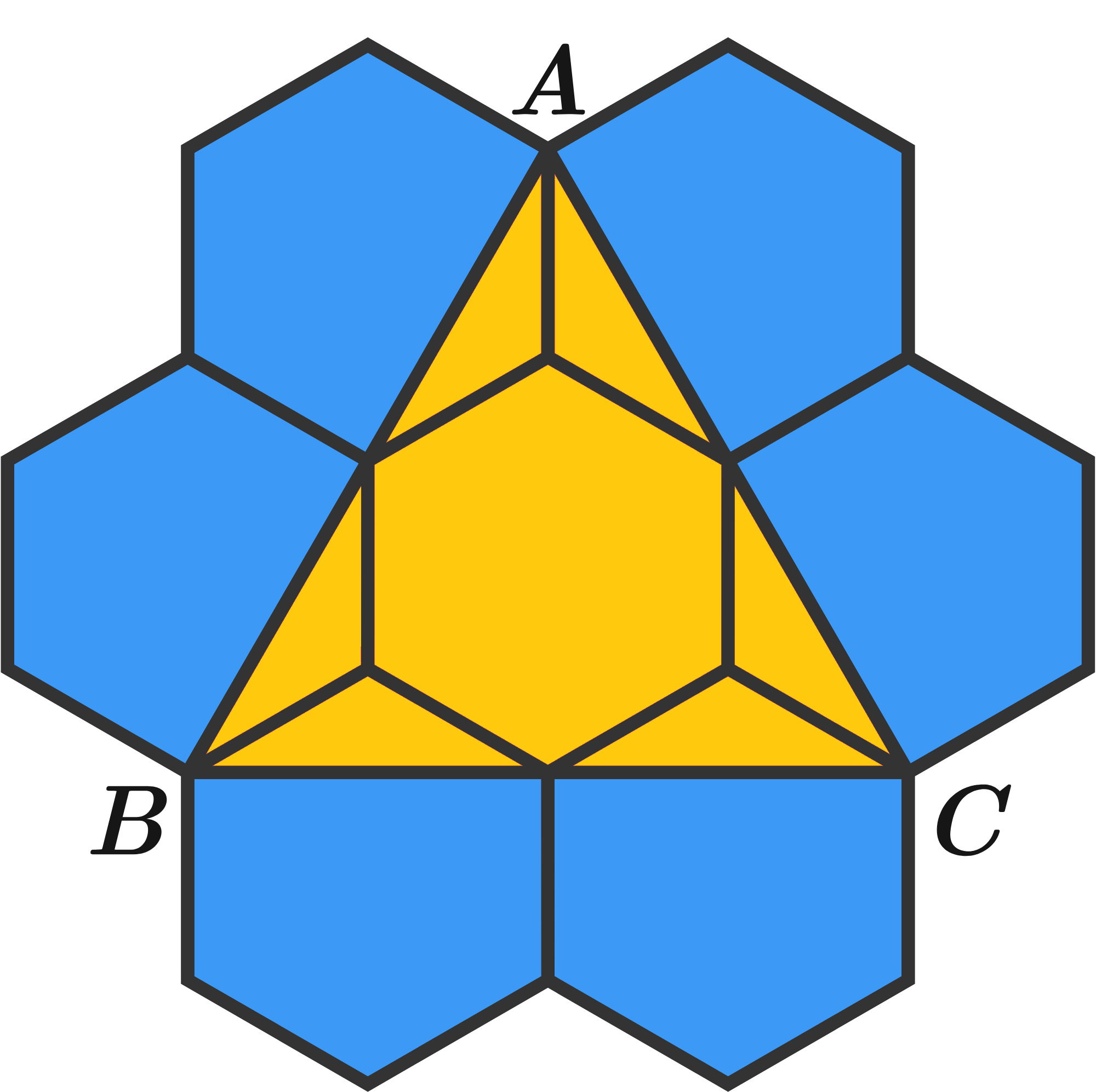

\(7\) identical hexagons are arranged in a pattern on the picture below. Each hexagon has an area of \(8\). What is the area of the triangle \(\triangle ABC\)?

In the triangle \(ABC\) the bisector \(BD\) coincides with the height. Prove that \(AB=BC\).