Problems

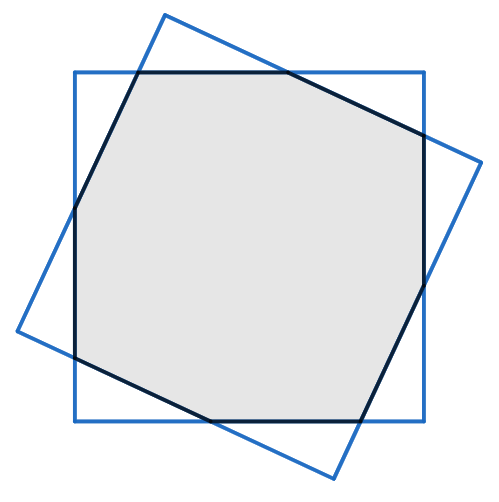

We have two squares sharing the same centre, each with side length \(2\). Show that the area of overlap is at least \(3\).

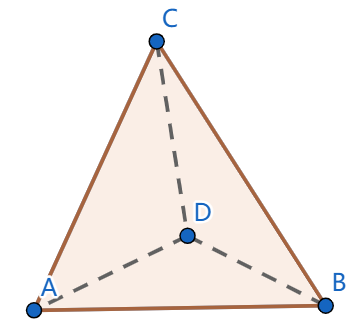

A regular tetrahedron is a three dimensional shape with four faces. Each face of a regular tetrahedron is an equilateral triangle. Describe all rotational symmetries of a regular tetrahedron.

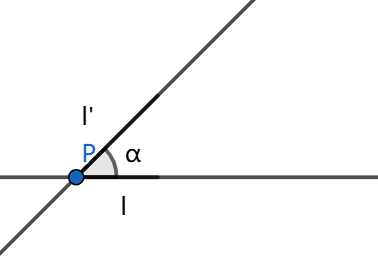

Two lines intersect at a point \(P\) at an angle of \(\alpha\). Show that a rotation in the plane around the point \(P\) through an angle \(2\alpha\) can be achieved by a reflection in one of the two lines followed by a reflection in the other line.

Show that a rotation about an axis on a sphere followed by a rotation about a different axis is again a rotation about some axis.

You have in your possession a rotation of the sphere about an axis \(l\) through an angle \(\alpha\neq k\times360^{\circ}\) for any integer \(k\).

Consider the following funny rules. Suppose you have a rotation \(r_1\) through an angle \(\theta\) around an axis \(m\) and a rotation \(r_2\) through an angle \(\theta'\) around an axis \(m'\). You can add to your possession each of the below:

the rotation \(r_1^{-1}\) through \(-\theta\) around \(m\);

the rotation \(r_2r_1\) obtained by doing \(r_1\) and then \(r_2\);

the rotation \(g^{-1}r_1g\), where \(g\) is any rotation of the sphere.

Can you get all the rotations of the sphere?

Let us colour each side of a hexagon using one of yellow, blue or green. Any two configurations that can be rotated or reflected onto each other will be the same colouring for us. How many colourings are there?

Let \(u\) and \(v\) be two positive integers, with \(u>v\). Prove that a triangle with side lengths \(u^2-v^2\), \(2uv\) and \(u^2+v^2\) is right-angled.

We call a triple of natural numbers (also known as positive integers) \((a,b,c)\) satisfying \(a^2+b^2=c^2\) a Pythagorean triple. If, further, \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\) are relatively prime, then we say that \((a,b,c)\) is a primitive Pythagorean triple.

Show that every primitive Pythagorean triple can be written in the form \((u^2-v^2,2uv,u^2+v^2)\) for some coprime positive integers \(u>v\).

What symmetries does a regular hexagon have, and how many?

Let \(X\) be a finite set, and let \(\mathcal{P}X\) be the power set of \(X\) - that is, the set of subsets of \(X\). For subsets \(A\) and \(B\) of \(X\), define \(A*B\) as the symmetric difference of \(A\) and \(B\) - that is, those elements that are in either \(A\) or \(B\), but not both. In formal set theory notation, this is \(A*B=(A\cup B)\backslash(A\cap B)\).

Prove that \((\mathcal{P}X,*)\) forms a group.