Problems

Elections are approaching in Problemland! There are three candidates for president: \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\).

An opinion poll reports that \(65\%\) of voters would be satisfied with \(A\), \(57\%\) with \(B\), and \(58\%\) with \(C\). It also says that \(28\%\) would accept \(A\) or \(B\), \(30\%\) \(A\) or \(C\), \(27\%\) \(B\) or \(C\), and that \(12\%\) would be content with all three candidates.

Show that there must have been a mistake in the poll.

You are creating passwords of length \(8\) using only the letters \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\). Each password must use all three letters at least once.

How many such passwords are there?

How many numbers from \(1\) to \(1000\) are divisible by \(2\) or \(3\)?

Three kinds of cookies are sold at a store: dark chocolate \((D)\), raspberry with white chocolate \((R)\) and honeycomb \((H)\). Here is a table summarizing the number of people buying cookies this morning.

| \(D\) | \(R\) | \(H\) | \(D, R\) | \(D,H\) | \(R,H\) | \(D,R,H\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people | 16 | 16 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

The column with label \(D,H\), for example, means the number of people who bought both dark chocolate and honeycomb cookies.

How many people bought cookies this morning?

At the space carnival, visitors can try two special attractions: the Zero-Gravity Room or the Laser Maze. By the end of the day:

\(100\) visitors have tried at least one of the two attractions,

\(50\) visitors tried the Laser Maze,

\(20\) visitors tried both attractions.

How many visitors tried only the Zero-Gravity Room?

We write all \(26\) different letters of the English alphabet in a line, using each letter exactly once.

How many such arrangements do not contain any of the strings

fish, rat, or bird?

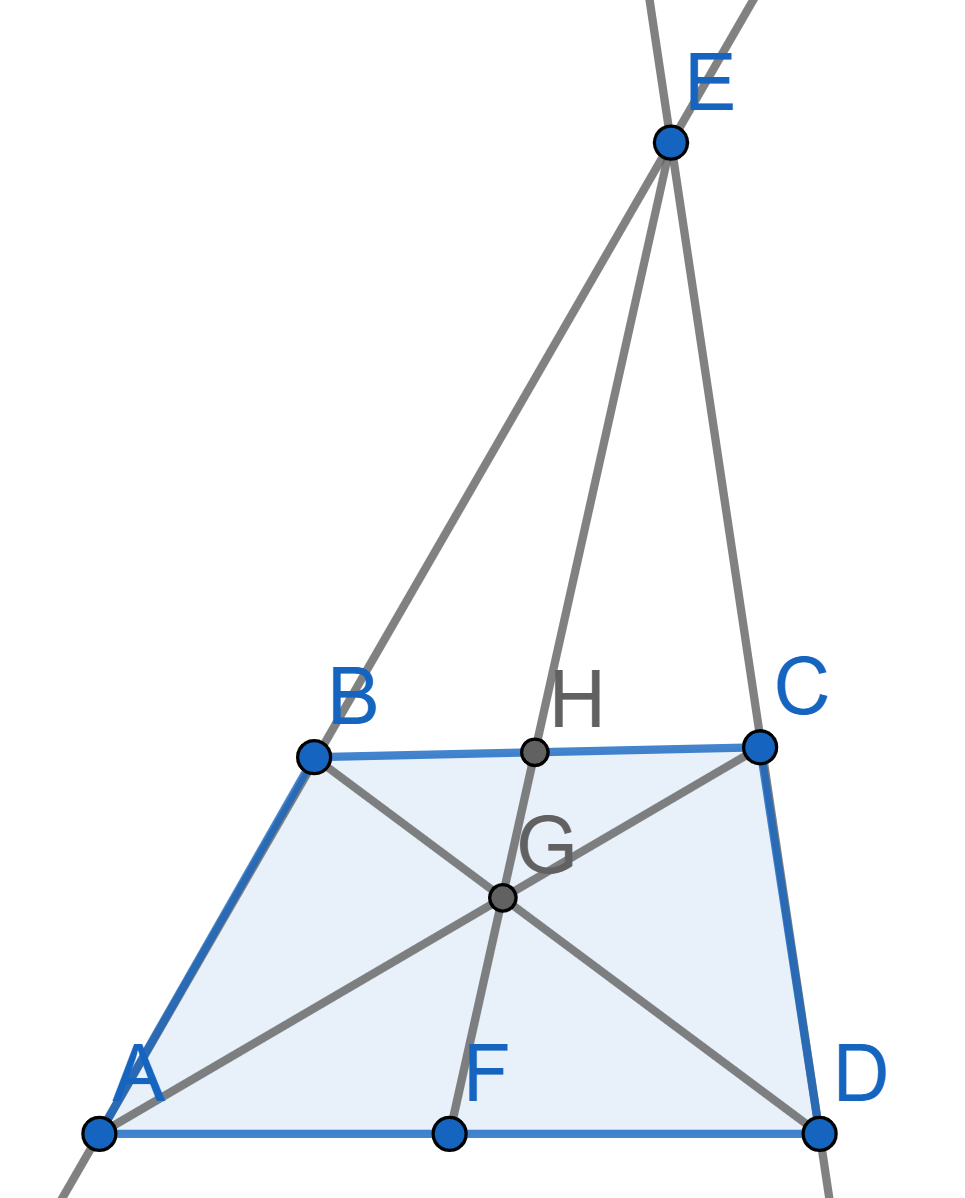

For a trapezium \(ABCD\), let \(E\) be the point of intersection of the sides \(AB\) and \(CD\), and let the point \(G\) be the point of intersection of the diagonals of the trapezium. Finally, let \(F\) amd \(H\) be the midpoints of the sides \(BC\) and \(AD\) respectively.

Prove that the points \(E,F,G,H\) lie on one line.

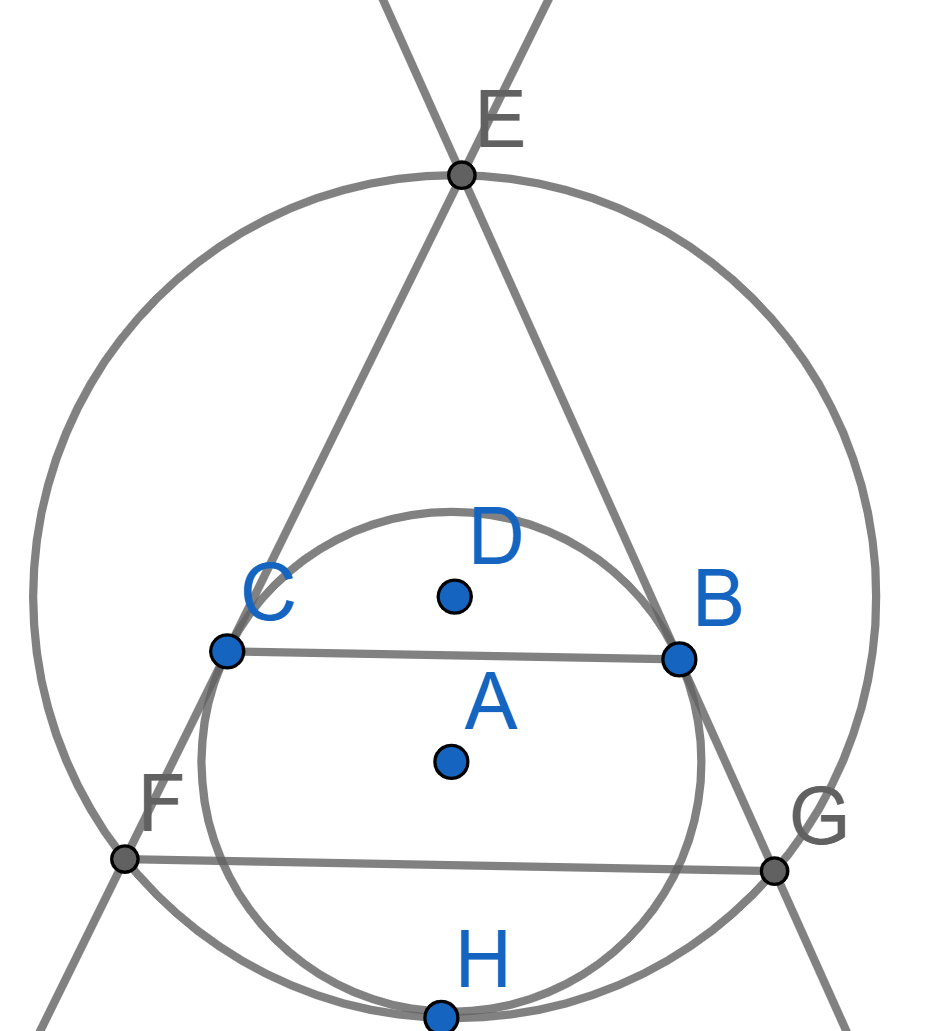

The triangle \(EFG\) is isosceles with \(EF=EG\). A circle with center \(A\) is tangent to the sides \(EF\) and \(EG\) at the points \(C\) and \(B\) respectively. It is also tangent to the circle circumscribed around the triangle \(EFG\) at the point \(H\). Prove that the midpoint of the segment \(BC\) is the center of the circle inscribed into the triangle \(EFG\).

Prove that under a homothety transformation, a polygon is transformed into a similar polygon.

Hint: to show this, why is it enough for you to show that homothety preserves angles and ratios?

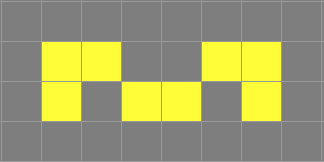

In the Game of Life, each cell in a grid is either alive or dead (in the diagram, yellow cells are alive). At each step, a live cell stays alive only if it has \(2\) or \(3\) live neighbours, otherwise it dies; a dead cell becomes alive only if it has exactly \(3\) live neighbours. A still-life is a pattern that does not change after any number of steps. Show that the following pattern cannot be turned into a still-life by only changing dead cells into alive cells.