Problems

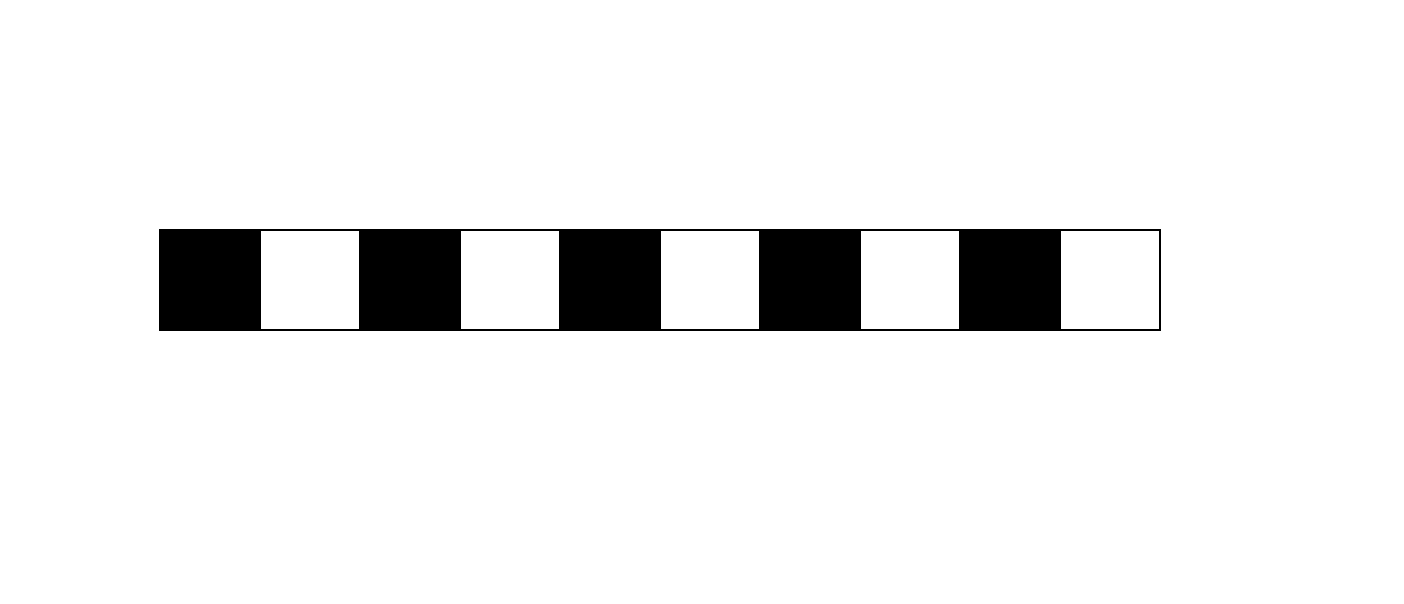

We are going to play the following game: look at the grid below, where each cell is painted black or white

choose any two cells that are next to each other and switch both of their colours. By switch, we mean: if a cell is black, change it to white, and if it is white, change it to black. Is it possible to turn the entire grid black?

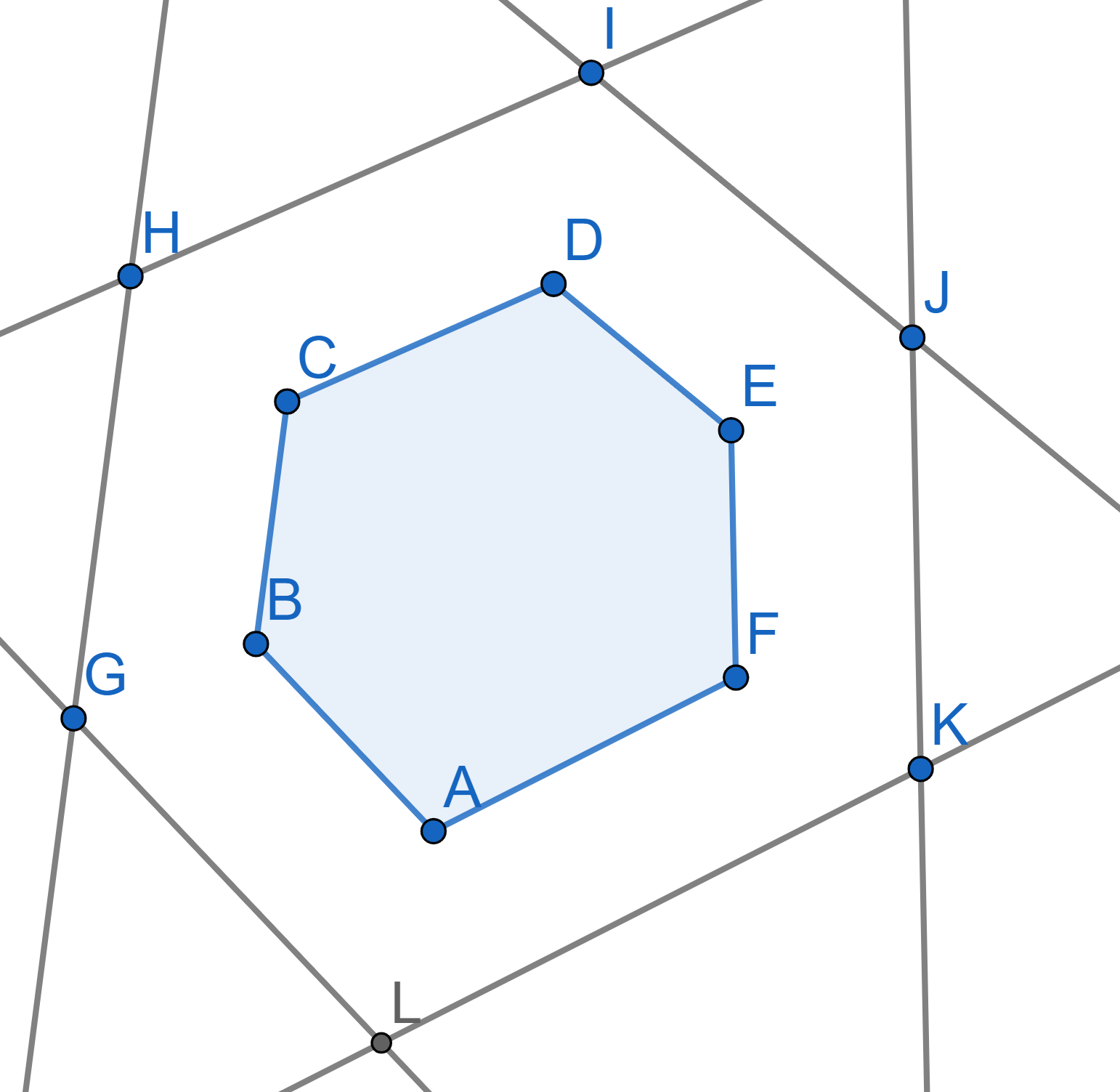

A convex polygon \(A_1A_2...A_n\) has the following property: if we parallel push all the lines containing the sides of the polygon for a distance \(1\) outside, we will obtain another polygon, similar to the original one with the corresponding parallel sides of the same ratio. Prove that one can inscribe a circle into the original polygon \(A_1A_2...A_n\).

For a triangle \(ABC\) denote by \(R\) the radius of the circle superscribed around \(ABC\), by \(r\) the radius of circle inscribed into \(ABC\). Prove that \(R\geq 2r\) and equality holds if and only if the triangle \(ABC\) is regular. For this problem, you may want to search about the “Euler Circle” online.

Under a homothety transformation, a line \(l\) is sent to a line \(l'\) which is parallel to \(l\).

Show that a homothety is uniquely determined by where it sends any two distinct points.

Consider a homothety with center \(O\) and coefficient \(k\). Which lines are sent to themselves by this homothety? (Hint: the answer will depend on \(k\))

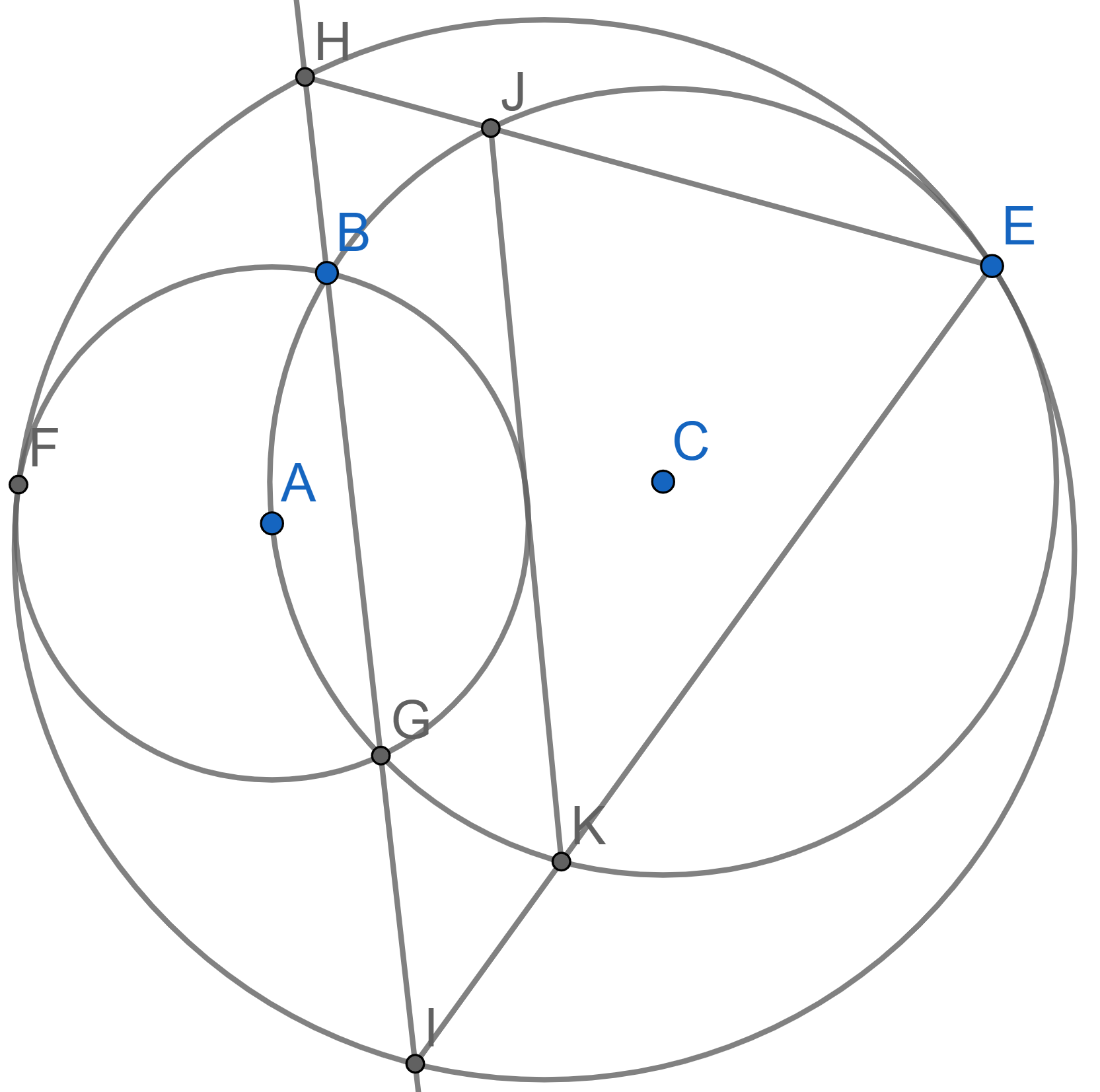

(IMO 1999) Two circles with centres \(A\) and \(C\) intersect at the points \(B\) and \(G\), moreover the circle with centre \(C\) goes through \(A\). A big circle is tangent to both given circles at the points \(E\) and \(F\) (see picture). The line \(BG\) intersects the big circle at the points \(H\) and \(I\). The segments \(EH\) and \(EI\) intersect with the circle with centre \(C\) at the points \(H\) and \(K\) respectively. Prove that the segment \(JK\) is tangent to the circle with center at \(A\).

On the first day Robinson Crusoe tied the goat with a single piece of rope by putting one peg into the ground. What shape did the goat graze?