Problems

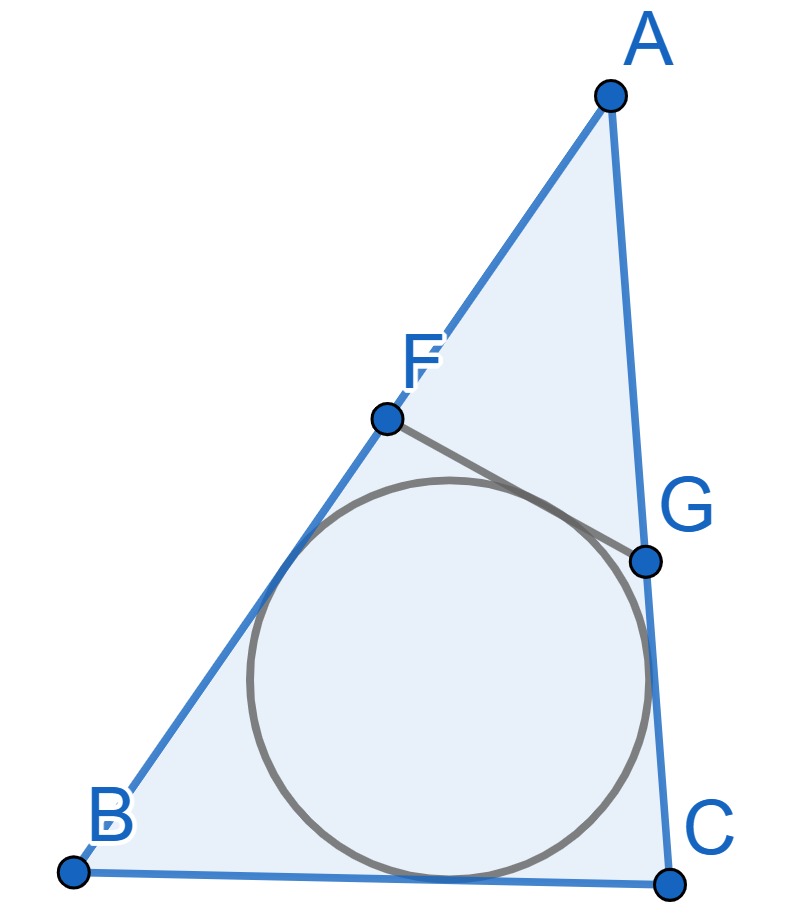

A circle is inscribed into the triangle \(ABC\) with sides \(BC=6, AC=10\) and \(AB= 12\). A line tangent to the circle intersects two longer sides of the triangle \(AB\) and \(AC\) at the points \(F\) and \(G\) respectively. Find the perimeter of the triangle \(AFG\).

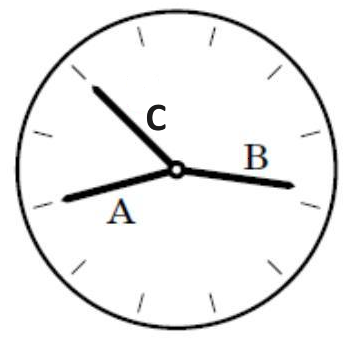

Liam saw an unusual clock in the museum: the clock had no digits, and it’s not clear how the clock should be rotated. That is, we know that \(1\) is the next digit clockwise from \(12\), \(2\) is the next digit clockwise from \(1\), and so on. Moreover all the arrows (hour, minute, and second) have the same length, so it’s not clear which is which. What time does the clock show?

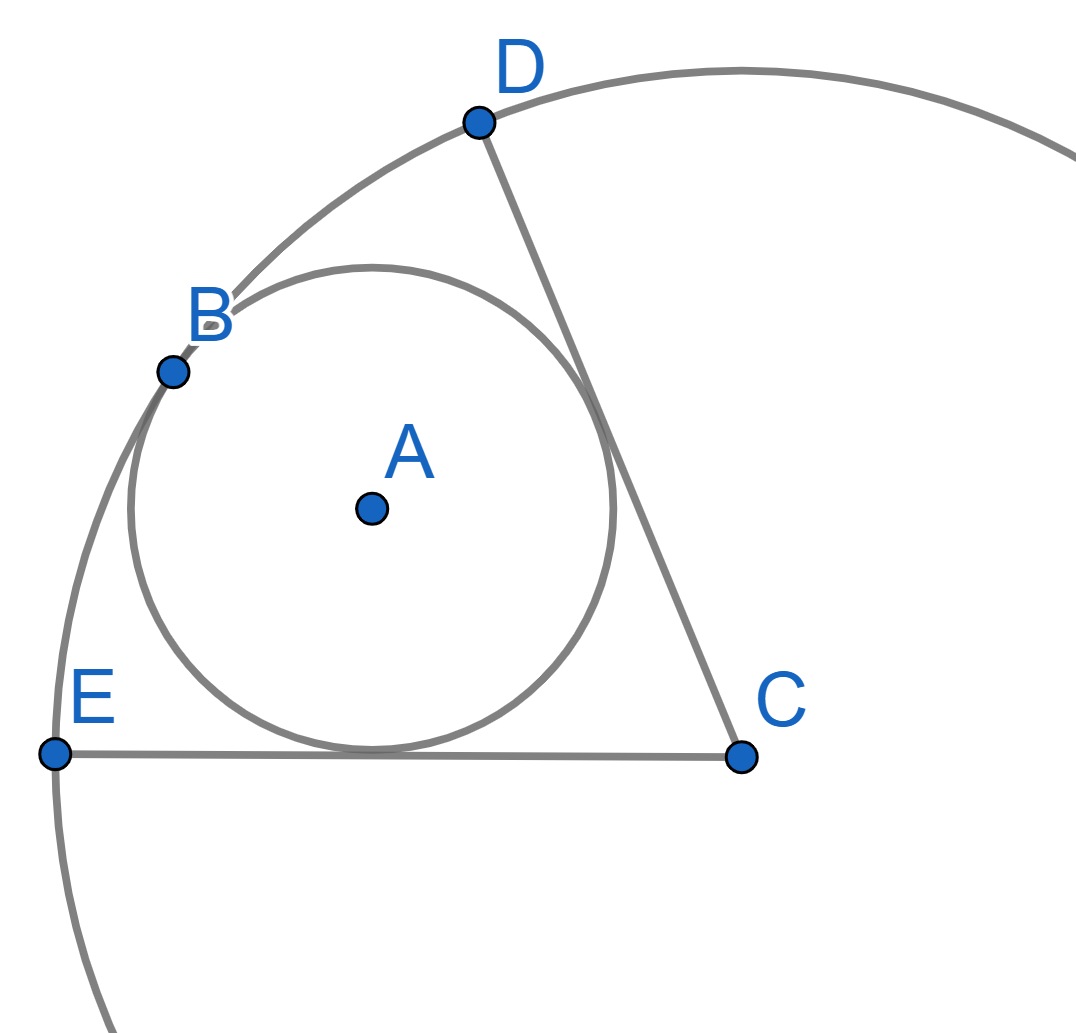

Two circles are tangent to each other and the smaller circle with the center \(A\) is located inside the larger circle with the center \(C\). The radii \(CD\) and \(CE\) are tangent to the smaller circle and the angle \(\angle DCE = 60^{\circ}\). Find the ratio of the radii of the circles.

For positive real numbers \(a,b,c\) prove the inequality: \[(a^2b + b^2c + c^2a)(ab^2 + bc^2 + ca^2)\geq 9a^2b^2c^2.\]

On a \(10\times 10\) board, a bacterium sits in one of the cells. In one move, the bacterium shifts to a cell adjacent to the side (i.e. not diagonal) and divides into two bacteria (both remain in the same new cell). Then, again, one of the bacteria sitting on the board shifts to a new adjacent cell, either horizontally or vertically, and divides into two, and so on. Is it possible for there to be an equal number of bacteria in all cells after several such moves?

Let \(p\) and \(q\) be two prime numbers such that \(q = p + 2\). Prove that \(p^q + q^p\) is divisible by \(p + q\).

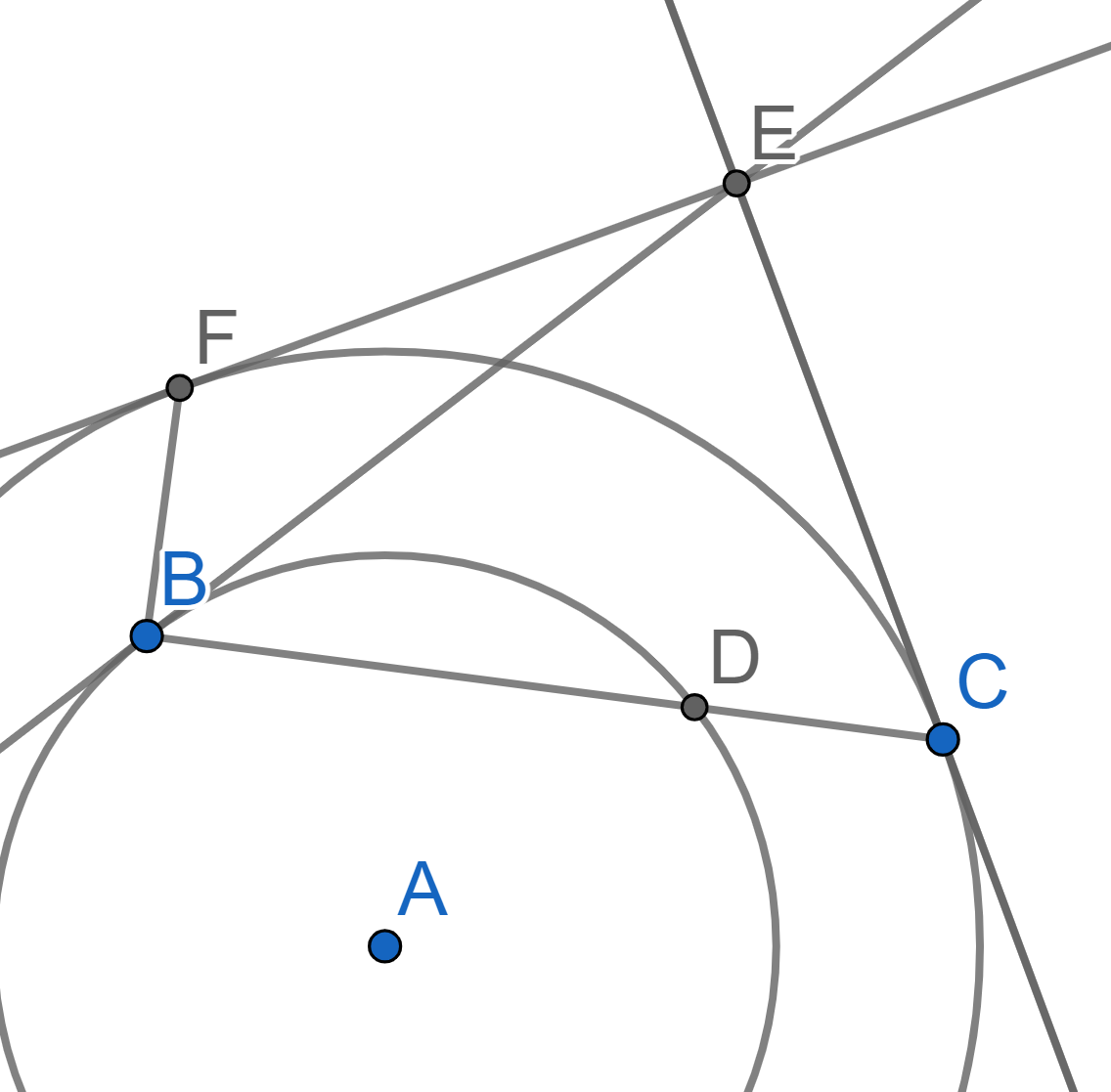

Let \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) be two concentric circles with \(C_1\) inside \(C_2\) and the center \(A\). Let \(B\) and \(D\) be two points on \(C_1\) that are not diametrically opposite. Extend the segment \(BD\) past \(D\) until it meets the circle \(C_2\) in \(C\). The tangent to \(C_2\) at \(C\) and the tangent to \(C_1\) at \(B\) meet in a point \(E\). Draw from \(E\) the second tangent to \(C_2\) which meets \(C_2\) at the point \(F\). Show that \(BE\) bisects angle \(\angle FBC\).

For any real number \(x\), the absolute value of \(x\), written \(\left| x \right|\), is defined to be \(x\) if \(x>0\) and \(-x\) if \(x \leq 0\). What are \(\left| 3 \right|\), \(\left| -4.3 \right|\) and \(\left| 0 \right|\)?

Let \(x\) and \(y\) be real numbers. Prove that \(x \leq \left| x \right|\) and \(0 \leq \left| x \right|\). Then prove that the following inequality holds \(\left| x+y \right| \leq \left| x \right|+\left| y \right|\).

There are \(n\) balls labelled 1 to \(n\). If there are \(m\) boxes labelled 1 to \(m\) containing the \(n\) balls, a legal position is one in which the box containing the ball \(i\) has number at most the number on the box containing the ball \(i+1\), for every \(i\).

There are two types of legal moves: 1. Add a new empty box labelled \(m+1\) and pick a box from box 1 to \(m+1\), say the box \(j\). Move the balls in each box with (box) number at least \(j\) up by one box. 2. Pick a box \(j\), shift the balls in the boxes with (box) number strictly greater than \(j\) down by one box. Then remove the now empty box \(m\).

Prove it is possible to go from an initial position with \(n\) boxes with the ball \(i\) in the box \(i\) to any legal position with \(m\) boxes within \(n+m\) legal moves.

Given a natural number \(n\), find a formula for the number of \(k\) less than \(n\) such that \(k\) is coprime to \(n\). Prove that the formula works.