Problems

Prove that each natural number \(n\geq 2\) can be uniquely written as a product of prime factors. More precisely, there are prime numbers \(p_1,\dots,p_s\) such that \(n = p_1\dots p_s\). Moreover, if \(n = q_1\dots q_l\) where \(q_1,\dots,q_l\) are prime, then \(s=l\) and after reordering we have \(q_1 = p_1,\dots,q_s=p_s\). This is the fundamental theorem of arithmetic.

The AM-GM inequality asserts that the arithmetic mean of nonnegative numbers is always at least their geometric mean. That is, if \(a_1,\dots,a_n\geq 0\), then \[\frac{a_1+\dots+a_n}{n}\geq \sqrt[n]{a_1\dots a_n}.\] Prove this inequality.

There are many proofs of this fact and quite a few of them are by induction. In fact, one of the most creative uses of induction can be found in Cauchy’s proof of the AM-GM inequality in Cours d’analyse.

Show that if \(1+3+5+7+...+97+99=50^2\), then \(1+3+5+7+...+97+99+101=51^2\). Don’t forget that \((a+b)^2=a^2+2ab+b^2\).

Prove that for all positive integers \(n\) there exists a partition of the set of positive integers \(k\le2^{n+1}\) into sets \(A\) and \(B\) such that \[\sum_{x\in A}x^i=\sum_{x\in B}x^i\] for all integers \(0\le i\le n\).

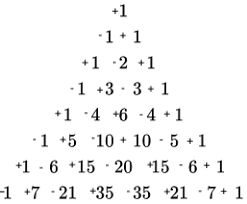

In Pascal’s triangle, what are the numbers in the diagonal next to the diagonal of ones?

In Pascal’s triangle, what is the sum of the entries in each row?

Oliver throws a fair coin three times. What are his chances of getting three heads, two heads and one tail, one head and two tails, or three tails?

In Pascal’s triangle, what numbers appear in the diagonal next to the positive integers?

Five friends get together and want to take a photo. They all agree that two of them should take a photo of the other three. How many ways can you choose the three people to be in the picture?

In Pascal’s triangle, what’s the sum of the numbers in each row when you put a minus sign in front of every other number?