Problems

Each whole number is painted either blue or yellow, with the following rules:

The sum of two numbers painted in different colours is painted yellow.

The product of two numbers painted in different colours is painted blue.

There is at least one number of each colour. What possible colours can the product of two blue numbers have?

We make a long list of numbers in the following way. We start with \(1\) and \(1\). After that, each new number is the last digit of the sum of the two numbers right before it. For example, the beginning of the list is \[1,\,1,\,2,\,3,\,5,\,8,\,3,\,1,\,4,\ldots\]

Show that, if we keep making numbers like this forever, the list must eventually start repeating in a loop.

Let \(P(x)\) be a polynomial with integral coefficients. Suppose there exist four distinct integers \(a,b,c,d\) with \(P(a) = P(b) = P(c) = P(d) = 5\). Prove that there is no integer \(k\) with \(P(k) = 8\).

For which natural number \(n\) is the polynomial \(1+x^2+x^4+\dots+x^{2n-2}\) divisible by the polynomial \(1 +x+x^2+\dots+x^{n-1}\)?

Let \(P(x)\) be a polynomial with integer coefficients. Set \(P^1(x) = P(x)\) and \(P^{i+1}(x) = P(P^i(x))\). Show that if \(t\) is an integer such that \(P^k(t)=t\) for some natural number \(k\), then in fact we have \(P^2(t) = t\).

(IMO 2006) Let \(P(x)\) be a polynomial of degree \(n > 1\) with integer coefficients and let \(k\) be a positive integer. Consider the polynomial \(Q(x) = P^k(x)\). Prove that there are at most \(n\) integers \(t\) such that \(Q(t) = t\).

A goofy robot named Zippity only speaks using \(0\)s and \(1\)s. Every message Zippity sends is made of \(10\) digits. How many different \(10\)-digit messages can Zippity send if each message must include exactly one run of five zeros in a row? For example, \(0011000001\) would count as a valid message, but not \(1001010001\).

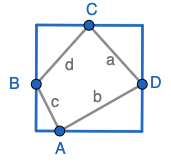

Four points \(A,B,C,D\) are chosen on the sides of a square of side length \(1\). The quadrilateral with vertices \(A,B,C,D\) has side lengths \(a,b,c,d\) as in the picture below. Show that \(2\leq a^2+b^2+c^2+d^2\leq 4\).

Let \(a, b, c\) be numbers such that \(a^2 + b^2 + c^2 = 1\). Show that \[-\frac12 \leq ab + bc + ac \leq 1.\]

An ordered triple of numbers is given. It is permitted to perform the following operation on the triple: to change two of them, say \(a\) and \(b\), to \(\frac{a+b}{\sqrt{2}}\) and \(\frac{a-b}{\sqrt{2}}\). Is it possible to obtain the triple \((1,\sqrt{2},1+\sqrt{2})\) from the triple \((2,\sqrt{2},\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}})\) using this operation?