Problems

There are \(n\) people at a royal ball. Every time three of them meet and talk, it turns out some two of them didn’t know each other before. Show that the maximum number of connections between the guests is \(\frac14 n^2\). If any guest \(A\) knows guest \(B\), then \(B\) knows \(A\), and this counts as one connection.

An animal with \(n\) cells is a connected figure consisting of \(n\) equal-sized adjacent square cells. A dinosaur is an animal with at least 2007 cells. It is said to be primitive if its cells cannot be partitioned into two or more dinosaurs. Find with proof the maximum number of cells in a primitive dinosaur.

What time is it going to be in \(2025\) hours from now?

Prove that the product of five consecutive integers is divisible by \(30\).

Prove that if \(n\) is a composite number, then \(n\) is divisible by some natural number \(x\) such that \(1 < x\leq \sqrt{n}\).

The natural numbers \(a,b,c,d\) are such that \(ab=cd\). Prove that the number \(a^{2025} + b^{2025} + c^{2025} + d^{2025}\) is composite.

Prove that for an arbitrary odd \(n = 2m - 1\) the sum \(S = 1^n + 2^n + ... + n^n\) is divisible by \(1 + 2 + ... + n = nm\).

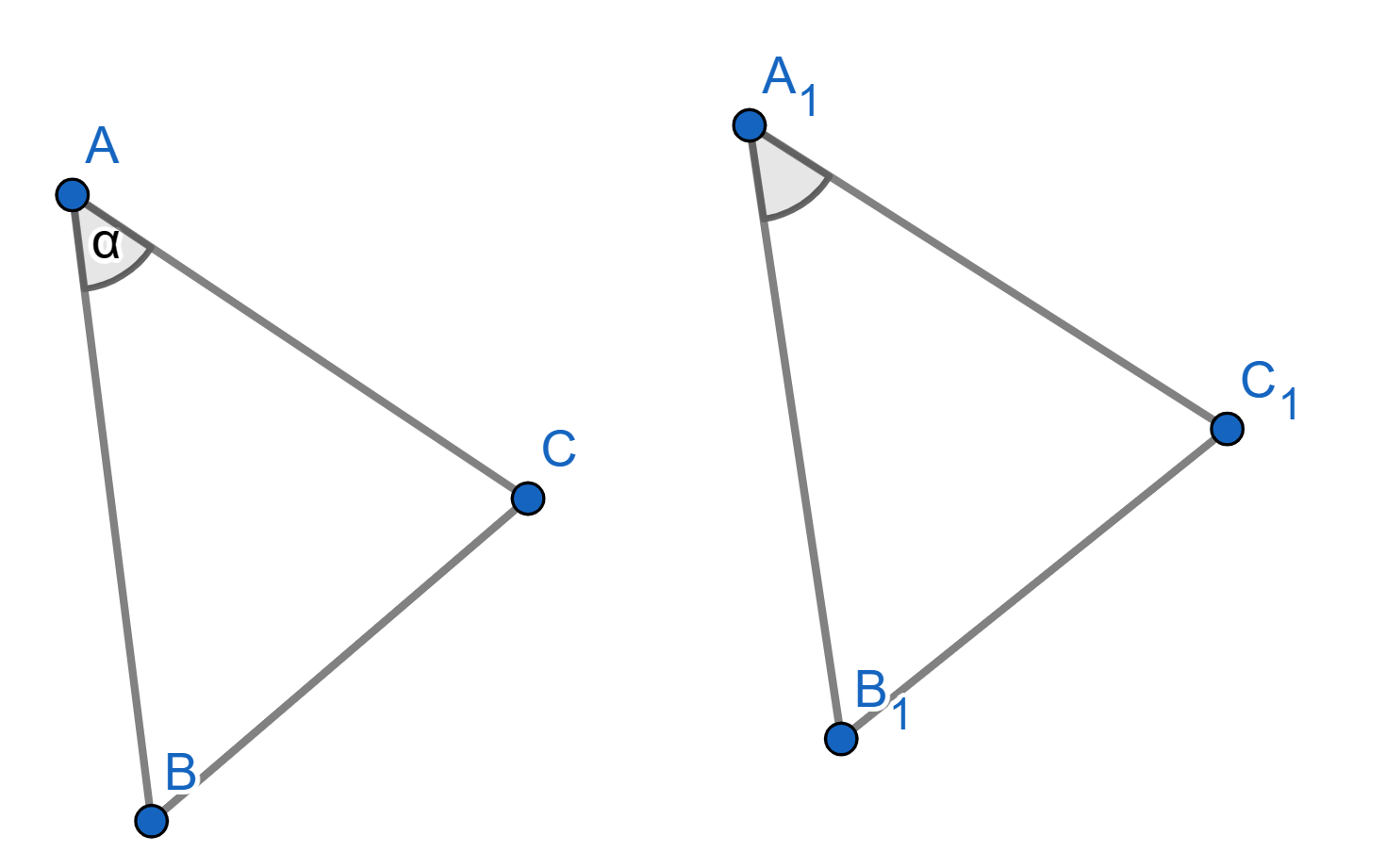

Let \(ABC\) and \(A_1B_1C_1\) be two triangles with the following properties: \(AB = A_1B_1\), \(AC = A_1C_1\), and angles \(\angle BAC = \angle B_1A_1C_1\). Then the triangles \(ABC\) and \(A_1B_1C_1\) are congruent. This is usually known as the “side-angle-side" criterion for congruence.

In the triangle \(\triangle ABC\) the sides \(AC\) and \(BC\) are equal. Prove that the angles \(\angle CAB\) and \(\angle CBA\) are equal.

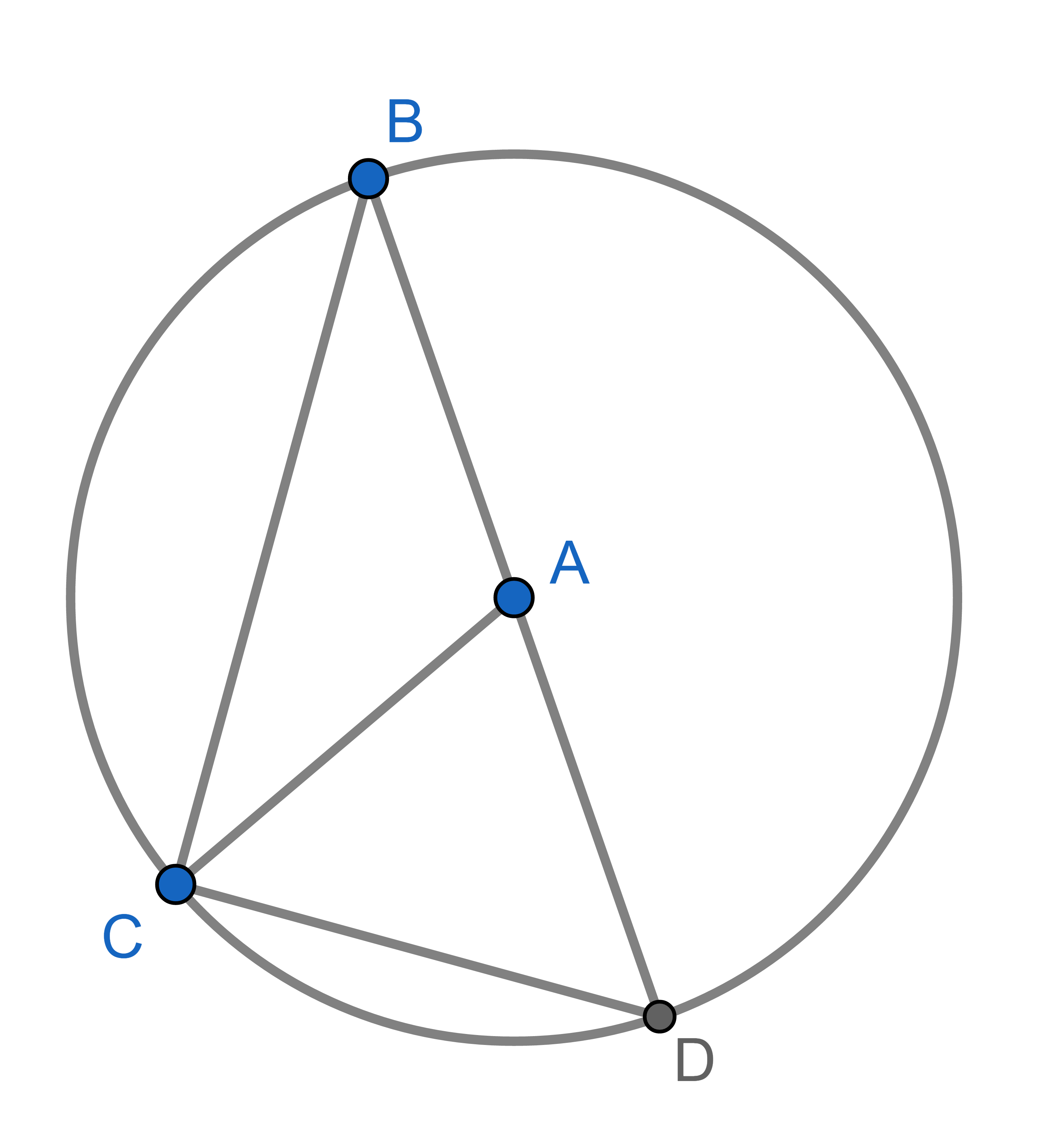

Point \(A\) is the centre of a circle and points \(B,C,D\) lie on that circle. The segment \(BD\) is a diameter of the circle. Show that \(\angle CAD = 2 \angle CBD\). This is a special case of the inscribed angle theorem.