Problems

Remember that two shapes are congruent if they are the same in shape and size, even if one is flipped or turned around. For example, here are two congruent shapes:

Cut the following shape into four congruent figures:

Welcome back! The topic of this sheet is: dissections and gluings. This means that we will take shapes, break them apart, and put the pieces back together to form interesting objects. Sometimes, we will also “glue" objects together and see how they can be used to construct other shapes. Let’s see a few simple examples:

Welcome back from the summer holidays! We hope you’re rested and ready for an exciting year of problems. Today we’re going to dive right into our first topic with a fun game called “Lights Out."

Imagine a grid of square buttons. Each square has a light that can be ON or OFF. When you press a square, that light flips, and so do the lights directly above, below, left, and right. In today’s pictures, dark blue means OFF and light blue means ON. If you want to try it at home, search “Lights Out (game)” on Wikipedia for an interactive version.

Before we start, let’s write three key words. After we see the examples, their meaning will be much clearer:

A light pattern is just which lights are ON or OFF on the board.

A plan is the collection of buttons you choose to press to make a pattern

A quiet plan is a plan that is not empty (it has at least one button on it) and when pressed, leaves the board looking exactly like it was before. For example: if the board starts all OFF and a quiet plan is pressed, then the board will still be all OFF.

Welcome everybody! In today’s session we will be talking about divisibility tricks. Recall that a number \(a\) is divisible by another number \(b\) if \(a\) divided by \(b\) is a whole number. Often, there are quick ways to check divisibility without doing the full division. For example, a number is divisible by \(5\) if and only if its last digit is \(0\) or \(5\). It is important to remember that this phrase “if and only if" actually means two things:

If a number is divisible by \(5\), then its last digit must be \(0\) or \(5\).

If a number’s last digit is \(0\) or \(5\), then the number is divisible by \(5\).

It is useful to think about this in terms of there being two directions. In today’s sheet we will see many more such tricks, and remember: usually you will need to prove both directions!

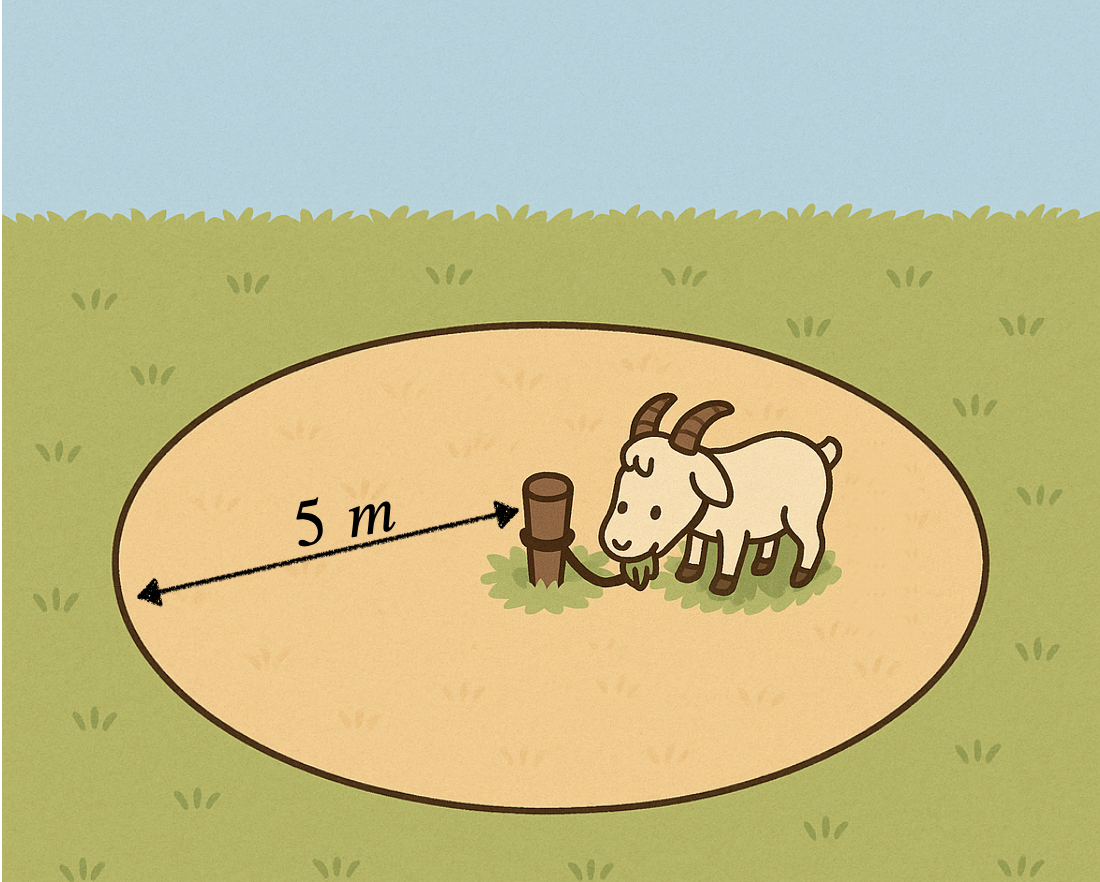

When Robinson Crusoe was stranded on his island, he found a goat and decided to keep it. To stop the goat from running away, he tied it to a peg in the ground with a rope. The goat wandered around happily, eating all the grass it could reach until the rope pulled tight. For example, Robinson noticed that with just one peg and one rope of length \(5\) meters, the grazed area was exactly a circle of radius \(5\) meters!

In this sheet we will explore what shapes the goat can graze when Robinson uses pegs, ropes, and even small sliding rings in slightly more complicated positions. In mathematics, the shape made by all points that satisfy a condition is called a locus (plural: loci). In our problems, the locus of the goat is the area it can graze. Before we begin, here are the rules of the game:

We will treat the goat as a single point, and the rope as a fixed length that cannot stretch, so the goat can graze any point it can reach before the rope is tight. A peg is simply a point in the ground that does not move. Let’s see some more interesting examples:

Often in maths we want to prove statements of the form “If A, then B.” For example: “If a number is divisible by \(4\), then it’s even.”

Usually, we prove such statements using something called a direct proof. In the example above, a direct proof would start by imagining we have some number — we don’t know which one — but we know it has the property “divisible by \(4\)”, and then using this information to work out that the number must be even.

However, this kind of direct reasoning can sometimes be tricky. Luckily, there’s another way! The idea is that a statement of the form “If A, then B” means exactly the same thing as “If not \(B\), then not \(A\).”

This second way of writing it is called the contrapositive, and we call “not \(B\)” the negation of \(B\). Here’s an everyday example: “If it rains, then I take my umbrella." is exactly the same as saying “If I don’t take my umbrella, then it’s not raining."

When we use this method in maths, we often say we’re proving by contrapositive: instead of proving “If \(A\) then \(B\)”, we prove “If not \(B\) then not \(A\).” Using this idea, to prove the example above, it would be the same as to prove the statement: ”If a number is not even, then it’s not divisible by \(4\)".

We sometimes write “If \(A\) then \(B\)” as \(A \implies B\), which is pronounced “\(A\) implies \(B\)”. Its contrapositive is: \(\text{not }B \implies \text{not }A.\) This way of thinking often makes a proof much simpler. Let’s see some examples to learn how to use this method.

One of the most powerful ideas in mathematics is that we can use letters — like \(a, b, n\) or \(x\) — to stand for numbers, shapes or other things. When we do this, we can reason about all such possible objects at once, without knowing exactly which number or shape we are really dealing with.

For example, the statement \[\text{``Let } a,b \text{ be numbers. Then } a+b=b+a."\] is true no matter what numbers \(a\) and \(b\) are. It tells us all of the following at the same time: \[3+5=5+3, \qquad (-10)+(-2)=(-2)+(-10), \qquad 7+0=0+7,\] and many more.

The rule \(a+b=b+a\) does not depend on the “three-ness” of \(3\) or the “five-ness” of \(5\) — it works for any numbers. Of course, we could not let \(a\) be a triangle and \(b\) be a tiger, because we do not know what it means to add a triangle to a tiger! Our rules only apply to objects for which the operations make sense.

This way of using symbols to express rules and patterns is what we call algebra. As long as we follow the rules that numbers follow, our reasoning will stay true. Today we will practise using these symbols to work with the algebra of numbers — it may take effort, but it is an important skill that will help you a lot in your mathematical journey.

One of the most important tools in maths is the Pigeonhole Principle.

You may have already met it before, but if not, let’s recap it quickly.

Simply put: the Pigeonhole Principle states that if you have \(n\) pigeons (or objects) that you want to

place into a number of pigeonholes (or containers) that is strictly

smaller than \(n\), e.g: \(10\) pigeons but only \(9\) pigeonholes, then there will be a

pigeonhole with at least two pigeons. Why is this true? Imagine that

every pigeonhole had at most one pigeon. Since we have \(9\) pigenholes in total, there would be at

most \(9\) pigeons, not \(10\), as we are told. Today we will see how

this principle can be used to solve problems about numbers and their

divisibility properties.

Before we get started, we need to recap a very important concept: if we

have two numbers, say \(a\) and \(b\), we can divide \(a\) by \(b\), and we will obtain a quotient

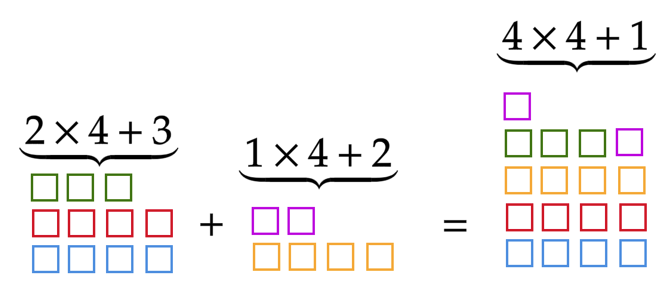

\(q\) and a remainder \(r\), and write \[a=q\times b + r\] for example: if we

divide \(9\) by \(4\), we can write \(9=2\times 4 + 1\), i.e: the quotient will

be \(2\) and the remainder will be

\(1\). A final key fact that we need to

recap is the following: imagine we want to divide two numbers, for

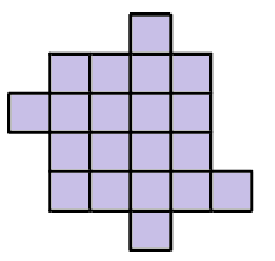

example \(11\) and \(6\) by the same number, say \(4\). We can write \[11=2\times 4 + 3\qquad \text{and}\qquad 6=1\times

4 + 2\] So we can imagine \(11\)

as two packs of \(4\) little squares

and \(3\) “left over" squares, and

\(6\) as one pack of four little

squares with \(2\) left over squares.

We can combine these \(5\) “left over"

squares into one new pack of four, with now one “left" over square. With

this way of thinking, we see that the remainder of a sum of two

numbers \(a\) and \(b\) is precisely the remainder of the

sum of the remainder of \(a\) plus

the remainder of \(b\).

A final remark: in today’s sheet, when we say positive whole numbers, or natural numbers, we will mean the numbers \(1,2,\cdots\)